By Girija Madhavan

Browsing through the internet, a photo from a bygone era caught my eye: Pandit Nehru with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, also called Chou Enlai [1898-1976]. His chiselled features and thick, black eyebrows, brought back memories of seeing him long ago, in person in Beijing [known as Peking earlier].

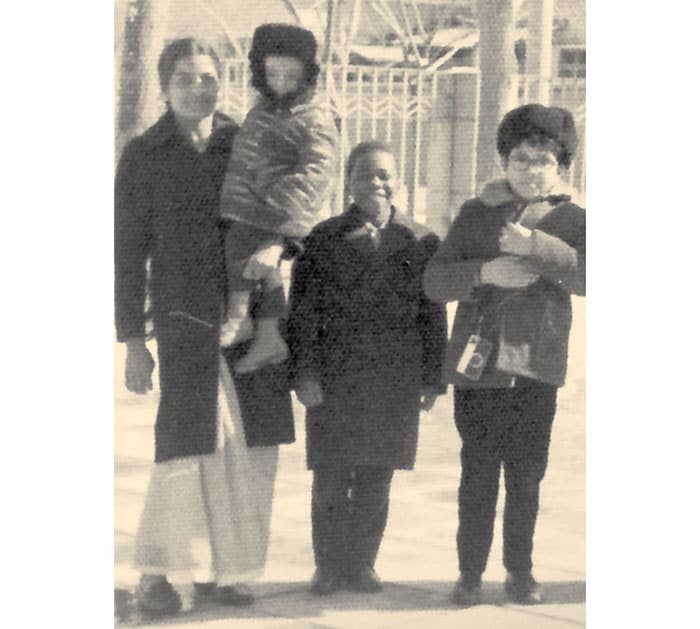

My husband, A. Madhavan and I were posted to the Indian Embassy, Beijing, from1968 to 1970 during the Cultural Revolution. Though the atmosphere was oppressive, with a hint of menace from the Red Guards, we Embassy-folk followed a regular routine of our own, working at the office and meeting other diplomats. The “Indian Embassy School” was set up by Mrs. Shaila Sathe [the wife of our Head of Mission, Ambassador Ram Sathe] in a wing of their Residence for our own Embassy children. The School operated till 2011. All of us wives in the mission helped out in whatever way we could. In time, Ugandan, Tanzanian, Iraqi, Rumanian and Yugoslav children joined the school; finally a little British boy. Excited to know I was an “Indian,” he asked me, “Do you like to fight with tomahawks or bows and arrows?”

I taught English and nursery rhymes. Anca Dorobantu, a little Rumanian girl, was my star pupil. There were two Chinese staffers also: “Ayi”, a cultivated, patrician-looking elderly woman who tidied the class rooms and helped with the smaller children, and Lao Li, the driver of the Embassy Microbus who ferried the teachers to the school. Ayi and Lao Li proudly wore Mao badges pinned to their boiler suits and attended gatherings to study “Mao Thought.” But Lao Li, a big man, was more interested in food, especially pork dumplings with chilli sauce from a favourite eatery.

We followed the rules laid down for foreigners; no driving beyond city limits and no photographing what the Chinese felt was sensitive, like the small character posters pasted on walls. Pastel coloured sheets of yellow, pink or blue, they carried strident political messages in black calligraphy in vertical columns, a signature of the times. The Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven and other sites were closed, a ploy by Premier Zhou Enlai to protect monuments and artefacts from damage.

“Chairman Mao” was the name that resounded over loudspeakers all day long in music and rhetoric. I knew little of Zhou Enlai. I found that his family was genteel but poor. He was adopted by an uncle whose wife, Mme Chen, taught him Mandarin and writing poetry in classical style. Graduating from Nankai School in 1917, he spent two years in Japan. “The Poems of Jhou EnLai” by Justin Theodra, contains an evocative poem he wrote on cherry blossoms and willows in Maruyama Park in Tokyo.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 impressed Zhou and he made his lifelong commitment to Communism when he was in France for a while. Back in China, he joined the Nationalists of Sun Yat-sen. He held office at the Whampoa Military Academy along with Chiang Kai Shek, who became an enemy after Zhou broke with the Nationalists. Though often in danger, Zhou Enlai escaped dramatically each time by changing residences and using disguises; as a librarian in Moscow or an antiquarian in Hong Kong.

On 16th October 1934, to extricate the Red Army from Nationalist attacks, Zhou Enlai and Mao organised the Long March, a strategic retreat from southern to northern China, covering 9,000 kilometres in 370 days. In a series of treks,35,000 men and 35 women marched, mainly at night, long lines of torches flickering over country tracks, a vivid image. The Long March remains an icon for the Chinese. The Chinese 5B rocket, the debris of which crashed into the Indian Ocean near the Maldives recently, was named “Long March.”

The journey ended at Yan’an in Shaanxi province, in the Loess plateau of north China. Yan’an is famous for its cave houses or “Yaodangs,” sustainable dwellings carved out of the hillside. Zhou Enlai and Mao Tsetung and their companions lived in these cave homes. Zhou married comrade Deng Yingchao in 1925. She is said to have decorated their cave windows with latticed rice paper screens. People still live in these caves, modernised now.

When the civil war ended, Chiang Kai Shek retreated to Taipei. Zhou Enlai became head of the Chinese Government, Mao Zedong the Chairman.

In Beijing, we could not meet officials or the local people. However, foreign diplomats were invited to formal receptions by the Chinese, gatherings held in an imposing hall. A large painting of Chairman Mao and many red flags formed the backdrop to a dais with a podium, guests seated in front of it at large dinner tables. A live orchestra played revolutionary music starting with the favourite “Dung Fang Hung” [The East Red]. When Zhou Enlai was the host, there was an exclusive fanfare played for him after which he would sweep on to the stage from the wings, clapping as a greeting to the assembled guests. At the end a toast was drunk. At the tables, a warmed wine called Shaoshing, fiery Mao Tai, a sweet red wine and champagne were served, orangeade for teetotallers. Once Zhou Enlai mingled among the guests to raise a toast. He came by our table and clinked glasses with us, a magnetic presence.

A banquet was served with starters like deep fried spinach, chicken, tofu, exotic mushrooms, crab rissoles and lobster claws succeeding one another until the highlight, Peking Duck, arrived. The China of Mao changed “The Four Olds,” but culinary traditions were meticulously maintained!

Our stay in Beijing was a unique experience, witnessing the travails of a country embroiled in a nationwide upheaval with far-reaching consequences. Of our nine postings abroad this assignment remains in the memory as the most challenging. Zhou Enlai, China’s “Grey Eminence,” died of cancer in 1976. A multifaceted individual, a brilliant military strategist and negotiator, he was one of the great figures of our times.

This post was published on May 17, 2021 6:05 pm