For over eight centuries, the silhouette of Chamundi Hill has defined the horizon of Mysuru. To the casual tourist, it is a scenic viewpoint and a place of temples and the demon’s statue; to the devotee, it is the sacred abode of the Divine Mother Chamundeshwari; and to the historian, it is a stone library detailing the rise and fall of dynasties.

Standing 1,063 metres above sea level, this 800-million-year-old geological formation is the crowning beauty of the South-East Mysuru. Yet today, this ancient sentinel is at a crossroads.

As urban sprawl climbs its slopes and concrete replaces its canopy, the Hill finds itself caught between the demands of modern tourism and the desperate need for ecological preservation.

The conversion of Chamundi Hill into a commercial hub poses not only a threat to its sanctity but also to its physical stability.

Geological & Mythological Foundation

The story of Chamundi Hill begins from a geological perspective. It is part of some of the oldest rock formations. For millions of years, it has stood silently, watching the city below expand.

In the local imagination, however, the Hill is born of myth. The epic battle between Goddess Chamundeshwari and the buffalo-demon Mahishasura and the victory of light over darkness is recalled during Dasara.

For centuries, the Hill was known as Mahabaladri or Mahabala Betta, named after Lord Mahabaleswara, the ancient deity of the Hill.

It is a historical irony that while the Mahabaleswara Temple remains the oldest structure on the Hill, it now sits in the shadow of the more prominent Chamundeshwari Temple, attracting only a few of the thousands who visit daily.

The Epigraphic Record

To understand the significance of the Hill, one must look at the inscriptions recorded there. The earliest fragmented record, dating back to 950 A.D., takes us back to the Ganga Dynasty.

Then comes the transition of the name in an inscription from 1127 A.D., during the reign of the legendary Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana. His inscription refers to the site as “Marballa Thirtha of Maisunadu.”

Nearly a century later, in 1211 A.D., the Hoysala King Vira Ballala referred to it as “Marbalesvara.” Nowhere in these early medieval records does the name “Chamundi” appear. The Hill was a centre of Shaivism (the worship of Shiva) long before it became the preeminent seat of Shaktism (the worship of the Goddess).

The rise of the Goddess is inextricably linked to the rise of the Wadiyars. As the family consolidated power in the 14th and 15th centuries, they adopted Chamundeshwari as their tutelary deity.

What was once a small Hilltop shrine began to transform into a grand complex, reflecting the growing prestige of the Mysore State of the Royals.

A Dynasty’s Devotion

The development of Chamundi Hill was a labour of love for the Maharajas. Every ruler left a mark, often linked to personal anecdotes that have since passed into folklore.

The earliest among them was Bettada Chamaraja Wadiyar (1513-1553). He constructed the “Hirikere” tank to ensure access to water for the Temple and the devotees.

Then came the legend related to “Bola” Chamaraja Wadiyar (1572-1576). The legend has it that while the King was climbing the Hill to offer prayers, a bolt of lightning struck near him.

While he survived, the shock caused his hair to fall out, leading to the nickname “Bola” (The Bald). The King viewed his survival as a divine blessing, further deepening the family’s bond with the Goddess.

The royal family’s vision further evolved with Dodda Devaraja Wadiyar (1659-1673) commissioning the most enduring works. He commissioned the famous 1,000 steps, a herculean task that allowed pilgrims to ascend the steep incline with greater ease and the erection of the 16-foot-high monolithic Nandi halfway up this path, at the 700th step.

Sculpted in 1664 from a single boulder of granite, this Nandi is a masterpiece of craftsmanship. He also established “Devarajapura,” a colony of 63 houses, which he donated to the priests and temple staff, ensuring that the spiritual life of the Hill was self-sustaining.

The Poetic Wilderness

To read the descriptions of the Hill from the 17th century is to imagine a different world. In 1648, the court poet of Kanthirava Narasaraja, Govinda Vaidya, wrote the Kanthirava Narasara Vijaya.

He describes the “Mahabaladri” as a sky-kissing mountain where the air was thick with the scent of flowering trees and the songs of birds. He speaks of yogis meditating in caves, oblivious to the mountain mists and of a forest so dense that it harboured every variety of flower and fruit-bearing trees.

He describes a flight of steps that wound upward “like a great ladder,” suggesting the existence of a much older flight of steps for the mountain’s ascent.

This wilderness persisted well into the modern era. Until the mid-20th century, the foothills were a sprawling thicket of scrub jungle and ancient burial grounds.

It was a place of mystery and, occasionally, danger. Leopards were not a rarity; they were residents. Maharaja Jayachamaraja Wadiyar, the last ruling prince, often stayed at the Lalithadri Palace and records mention him having to deal with leopards that strayed too close to human settlements with a gun in his hand.

Perhaps the most missed feature of this era is the ‘Horse-Shoe Valley.’ A section of the Hill took the shape of a horseshoe and hence the name.

This natural amphitheatre on the Hill once acted as a catchment for monsoon rains, creating a delicate waterfall that fed into a pristine pool at the foot of the Hill. Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV would often retreat to a simple stone bench overlooking this Valley, finding in its silence peace and wisdom to govern his State as ‘Rajarishi.’

Lady Dufferin’s Ascent

The Hill also captivated foreign visitors. In 1886, Lady Dufferin, the wife of the British Viceroy in India, visited Mysuru and left a vivid account of her experience in her travel diary.

In an age before the motorable road, she was carried up the 1,000 steps in a jhampan (a covered sedan chair) borne by twelve men. Her diary captures the rhythm of the climb: “They chanted on their way up… a wild sort of song, which sounded very inspiring.”

She describes the view from the top as “sublime,” though she admits the descent was “fatiguing and slippery.” Her stop at the Nandi for a photograph with the local priests remains a poignant snapshot of the intersection between Victorian curiosity and Indian tradition.

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, “development” was carried out with a sense of aesthetic responsibility. Records show the existence of these two temples on the Chamundi Hill for a long time. The other temples, like the Narayanaswamy, are of a modern period.

A pivotal era of transformation occurred during the reign of Mummadi Krishnaraja Wadiyar. A fervent devotee of the Goddess, Mummadi did not merely provide financial patronage; he left a personal legacy, installing his own Bhakta Vigraha (devotional statue) alongside those of his queens within the temple precincts, forever marking the royal family’s presence as humble servants of the deity.

Mummadi also built a Palace of modest size on the Hill. This allowed the royal family to stay in the presence of the Goddess, further cementing the Hill as a primary residence of the spirit rather than just a destination for a day’s excursion.

When Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV built the motorable road, the Lalithadri Palace and the iconic Mahishasura statue, he ensured they blended with the topography. Even the electric lights he installed were arranged in a specific arch known as the Shiva Dhanus (Shiva’s Bow), which glowed like a celestial weapon when viewed from city below.

Today, that symmetry is gone. In its place is a haphazard forest of electric poles. The recent push for tourism has brought with it a deluge of problems — concrete structures, plastic waste, unregulated shops and parking lots and more.

Environmentalists warn that the Hill is fragile. The granite slopes, while seemingly sturdy, rely on a delicate balance of vegetation to prevent soil erosion and landslides, which have become increasingly common in recent monsoon seasons.

The conversion of Chamundi Hill into a commercial hub poses not only a threat to its sanctity but also to its physical stability.

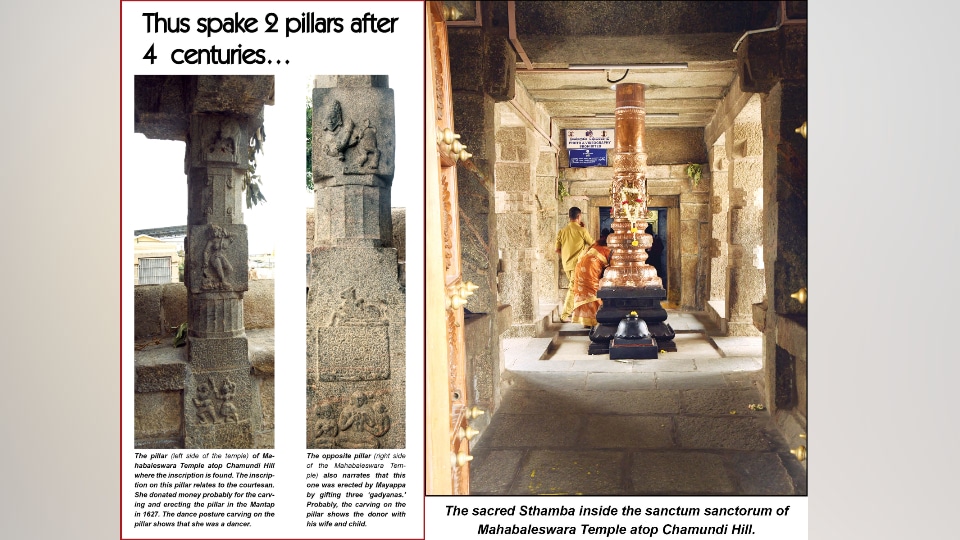

Thus spake 2 pillars after 4 centuries…

The two stone pillars in the oldest temple atop the Chamundi Hill — the Mahabaleswara Temple — reveal interesting details while standing mute for four centuries. The Northern-side stone pillar at the entrance of the Mantapa has a relief of two dancers. The inscription above this dancing figure says that Mayidevi is the courtesan or Patra of God Mahabaleswara of the Hill and her daughter Nagasambu had this pillar erected by donating three-and-a-half ‘gadyanas’ or gold coins on Nov. 28, 1627

The inscription also indicates that this is the third pillar erected at the four-pillared entrance porch. Of the two figures, probably the right one is of Mayidevi, the courtesan of the God Mahabaleswara, dancing to the beat of the drum being played by the musician standing next to her. It is interesting to note that this temple had the practice of having courtesans in the 17th century.

The opposite pillar also narrates that this one was erected by Mayappa, son of Mayaguru, of Darasivala, on the same date as the Northern-side pillar, by gifting three ‘gadyanas’. Probably, the carving on the pillar shows the donor with his wife and child.

The date of the inscription clearly proves that this four-pillared entrance porch of the Mahabaleswara Temple was constructed in the early 17th century, post-Vijayanagar period — the third stage of its development after the Gangas and the Hoysalas and in all probability some of the chiefs of these dynasties, including Cholas, visited this ancient temple.

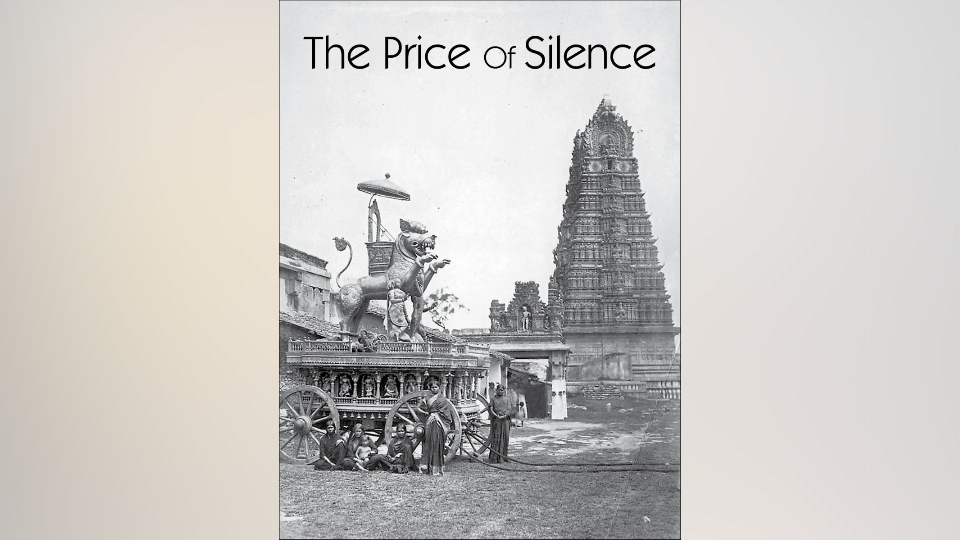

The Price Of Silence

The Chamundi Hill is more than a collection of temples; it is the lungs of Mysuru and the keeper of its history. From the ancient “Marballa Thirtha” to the modern cultural symbol of Dasara, the Hill has given much to the people of Karnataka.

However, the price of modern development may be too high and further development may be dangerous. The wild songs heard by Lady Dufferin have been replaced by the drone of the engines of the vehicles that carry the tourists and the devotees in hordes.

The ‘Horse-Shoe Valley’ is marred by construction. Vigilant stakeholders — locals and environmentalists — are concerned over the risk to the crowning beauty of Mysuru.

The Goddess may still reside on the peak, but the pristine paradise she once inhabited is fast becoming a memory. We tend to forget that some places are meant to be climbed with reverence, not paved with concrete.

Recent Comments