By Girija Madhavan

I have lived in many houses abroad before returning to settle down in my hometown of Mysuru in 1995. Each was a temporary home, a haven, claiming a place in my memories and sentiment; some in alien land and others in friendlier ambiance. But the house that remains in my mind as a dream-like experience, wreathed in little mysteries, is the one I lived in for just twenty days, in a dusty lane or “Hutung” in the heart of Peking (now Beijing).

The house was just number “7” on a lane named “Kung Yuan Hsi Chieh”. It branched off the Chang’an Avenue (Everlasting Peace) which cuts through the heart of the city, past the Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City.

Sent to the Indian Embassy in Peking in 1968, my husband, seven-year-old son and I travelled there via Hong Kong. A train took us to the border of the People’s Republic of China. We crossed from Lowu on the Hong Kong side, to Shumchun in China, on foot. The country was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, a contrast to Hong Kong which was then a flourishing British Crown Colony.

Woman wheeling a wickerwork pram.

In contrast to the stylish youth of Hong Kong, Chinese men and women wore patched blue “Boiler” suits; sported sensible haircuts or plaits. They called themselves “Red Guards”, young revolutionaries. The walls were pasted with posters denouncing reactionaries and capitalists. The train relayed revolutionary music and readings from the works of Chairman Mao Zedong during the two-day journey. Foreigners and diplomats were viewed with suspicion. Some Indian diplomats had been attacked. The atmosphere was one of underlying menace.

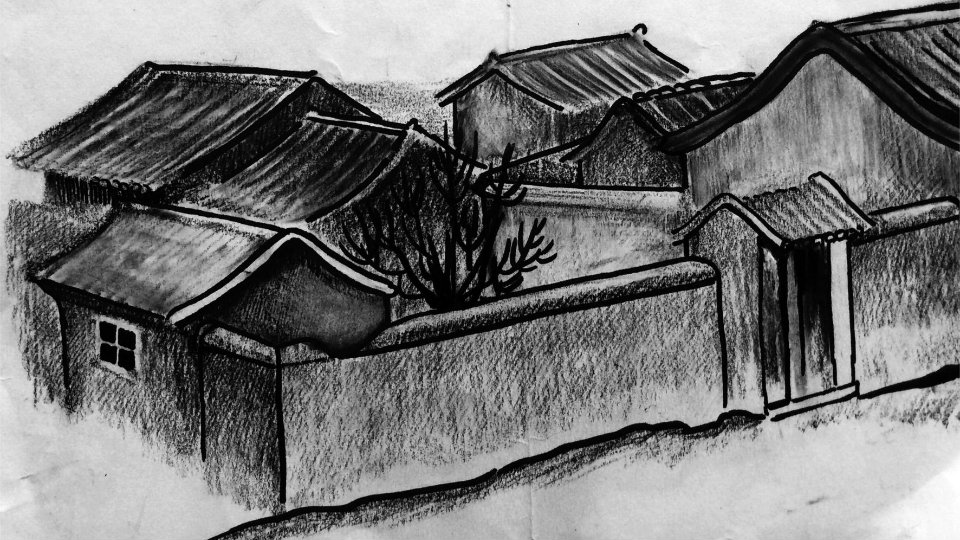

We reached Beijing in late March, wintry trees still bare-branched. Cold winds from the Gobi desert blew in dust, creating a grey background for the red flags and pastel-coloured posters covered with black calligraphy. We were taken to the house in which we were to stay. To the right Chinese dwellings with high outer walls and sloping convoluted roofs were faceless, anonymous.

Our house had been leased to the Indian Embassy for many years and senior Indian diplomats like Ambassador T.N. Kaul had once lived in it. We were happy the lease had been renewed as few foreigners could reside outside diplomatic enclaves. An ornate red gate was guarded by a militia-man in a uniform of green jacket and dark blue trousers, holding to his chest the “Little Red Book” of Chairman Mao’s Thoughts, a practice given up years later.

The house was a blend of Chinese and Western architecture, said to be built a Chinese general for his concubine. A colourful frieze decorated the walls and fireplace. Wrought iron doors led out to a porch where a wisteria creeper bloomed on a pergola. Beneath it a niche in the wall held a weather-beaten statue of Kuan Yin, Goddess of Mercy. A fish pond with dragon-headed water jets, garden lanterns with yellow glass panels and plum trees ranged against the far-wall formed the inner courtyard. I imagined the tracery of branches covered with white blossoms in spring.

Children in procession.

From the garden I could hear the sounds of the city – the tinkling of cycle bells, the laughter of children at play, the clip-clop of hooves, the crack of a whip as cart men urged on their horses, the three wheelers taking cabbages to the market. I used to go outside the gate to put refuse in a wheelbarrow meant for that purpose. I saw small children in procession waving their little fists to revolutionary chants. Old women with rusty black jackets and tapered pants would wheel infants in wickerwork prams, hobbling on feet as small as hooves. I realised that these were the last of the women with bound feet from olden times.

But the guard’s disapproving glare made it hard to linger outside. Further I collected a crowd of onlookers, unused to foreigners, staring at me. The guard dispersed them curtly, “Tso! Tso! Tso!” (Go away!) He was always craning his neck to look at the roof of the neighbouring house where a young boy could peer over the parapet and look into ours. When I once greeted the boy, he replied with an enthusiastic “Ni Hao! Ni Hao! Ni Hao!”; only to be sternly admonished by the Sentry. When once or twice an adult also appeared on the terrace to look into our home, his patience wore thin.

Our luggage arrived as a crowd from the neighbourhood watched. We unpacked and settled in. Soon we received a message from the Diplomatic Personnel Service Bureau, the wing that dealt with diplomats. Our house was deemed to be structurally unsafe for us to live there any longer. We were to move immediately to San Li Tun, a diplomatic enclave.

The Cultural Revolution, with all its tragedies and repercussions is now history – the sights and sounds of the city are relegated to the archives of memory. We witnessed a country in turmoil, replaced now by the Beijing of sophisticated, well-to-do people with sleek cars, of powerful politicians. I have no photographs as in those troubled times as cameras were viewed with deep suspicion. I only have images in my memory and some old sketches to share, to evoke that lost world.

Recent Comments