By Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik – Author, Speaker, Illustrator, Mythologist

Come Diwali, everyone revisits the story of this festival. It is what people do during festivals, trying to understand their origin. Some seek rational explanations: it is harvest time, and so time to party, for example. Some are happy with narrative explanations that are indifferent to reality: it is when Ram returned to Ayodhya. It is the latter which is far more enchanting and hence far more popular. And the more popular a festival, the richer the stories. Diwali is a case in point. Everybody agrees that Diwali is a festival of lights, and sweets, and crackers. Of course, with rising noise and dust pollution, the noisy part of the festival is gaining much disrepute. This is one global Hindu festival that American Indians are at pains to tell meets with the approval of the US President. But, why is this festival celebrated?

In India, festivals come into two clusters based on the summer and winter harvests. And so, there are festivals in spring, followed by festivals in the post-monsoon autumn. Diwali falls in the latter category. And it is full of narratives. The most popular myth associated with Diwali is that it is when Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth, arrives in the house and so lights are lit, and houses are cleaned, and decorated with floor and wall paintings, as she is drawn to illuminated, beautiful and clean spaces. This makes Diwali a Goddess festival. In Bengal, she is worshipped in her most primal form, as Kali, on the main festival, which falls on the full moon night. That night is also associated with gambling, reminding everyone that Lakshmi is drawn to people who are either skilled or lucky.

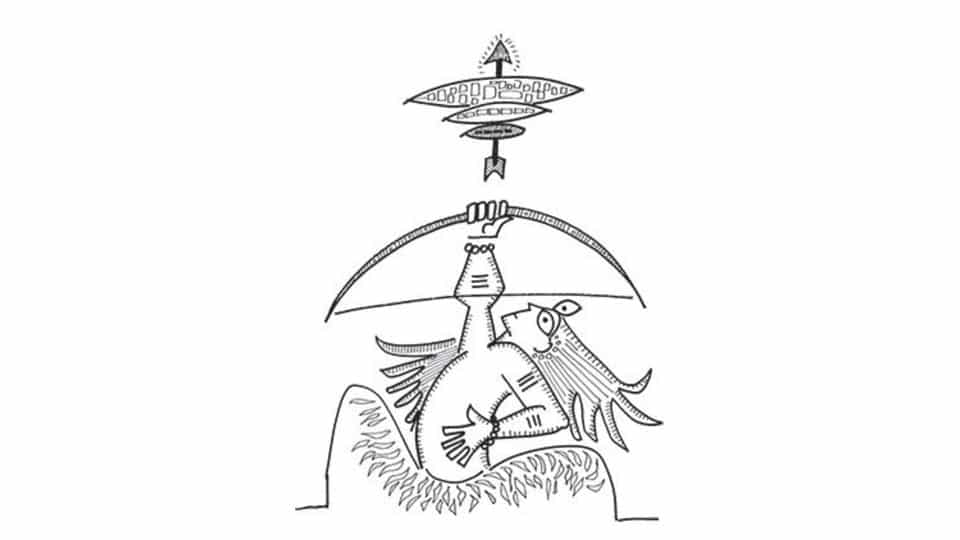

The festival is also linked with various forms of Vishnu. His triumph earns him the love of Lakshmi. And so, on the 14th day of the waxing moon, one celebrates, especially in Deccan region, the festival of Krishna killing the asura Naraka, who is also Vishnu’s son by Bhu-devi. And, on the first day of the waning moon one celebrates the defeat of Bali-asura by Vamana, who shoves him to the realm reserved for asuras, Patala, under the ground. That a similar story is told in Kerala for Onam festival leads to confusion and rationalisation, such as ‘on Onam he rises from earth and on Diwali he is sent back’, thus alluding to old cyclical fertility myths, political arguments notwithstanding. Of course, Diwali is also the victory celebration of the Goddess, who, having killed Mahisha-sura and rested to rid herself of her violent ‘chandi’ form, restores her auspicious fortune-attracting ‘mangala’ form. For Ram worshippers, it is the day when Ram returned home from his exile on his Pushpak-vimana and lights were placed in houses to help the celestial ‘aeroplane’ land. The final day is reserved for Lakshmi’s brother Yama, who is the Hindu God of Death, as well as the Hindu God of Accounting. The festival season that begins with Ganesha’s worship and then ancestor worship (Pitr Paksha), thus is drawn to an end. But what about Shiva? Shiva is an outsider God. In Vedic rituals, he comes after the yagna has concluded with his dogs and ghost companions to claim the leftovers. Likewise, he has his own Diwali, the Dev Diwali, on the full moon (Kartik or Tripuri Purnima) that follows, which was Nov. 3 this year. Even this is a victory celebration, for the Gods worship Shiva, who shot down three flying asura cities with a single arrow.

e-mail:[email protected]

Recent Comments