By Dr. S.N. Prasad, Amateur Astronomer, Mysuru

Comet C/2022 E3 [ZTF] has been making the news for quite some time, though very few people have actually seen it with the unaided eye. The comet’s sighting from the outskirts of Mysuru city was first reported in Star of Mysore a fortnight ago, on Jan. 30.

Now, on its outward journey from the solar system, after its closest approach to the Earth on Feb. 1, some of us (see picture) got together to get a farewell telescopic glimpse of the comet on the night of Feb. 13 at Krishnamurthy’s home, not too far from the city.

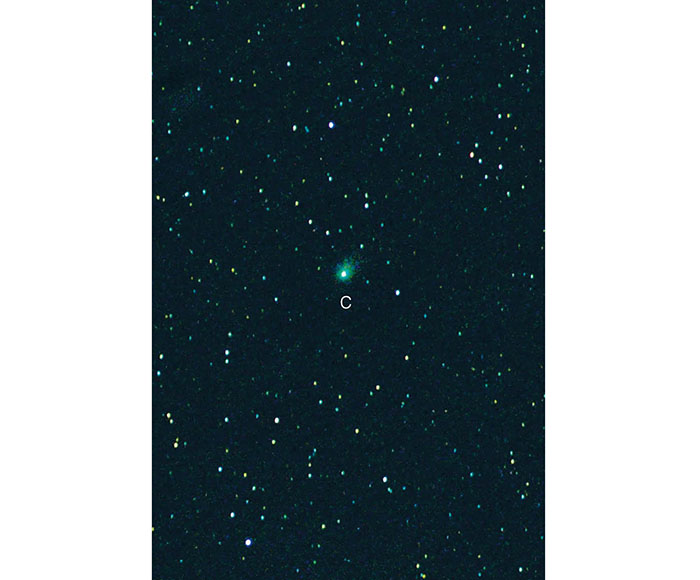

Though its brightness is diminishing noticeably day by day, we were able to see it quite clearly, close to the well-known bright star Aldebaran (Rohini) in the constellation Taurus, through his Celestron 8” telescope, with a wide field eyepiece. Its precise location at that time is shown in the accompanying star chart. However, it was not possible to see it with the naked eye, though barely visible through binoculars. Again, we were not equipped to capture a presentable photograph. The picture of the comet shown below was taken around the same time by Vikas Shukla near Pune and is reproduced with grateful thanks to him.

Comets are described quite literally as dirty snowballs, made up of a mixture of dirt, water ice, methane, ammonia, carbon dioxide and other frozen gases. They originate in the vast ‘Oort cloud’ surrounding the solar system at its outer reaches, about a light-year away.

When they get close to the Sun, the frozen gases making up the head of the comet vaporise, get detached and are pushed away by solar radiation pressure to form the distinctive cometary tails pointing away from the Sun.

Two types of tails are noticeable, the straight ones being plasma (ionic) tails and the curved ones the dust tails. A recent NASA picture of Comet C/2022 E3 [ZTF] reproduced here shows both forms of tails clearly. The generally irregular and large head or ‘coma’ of the comet consists mainly of frozen stuff, with rocky cores.

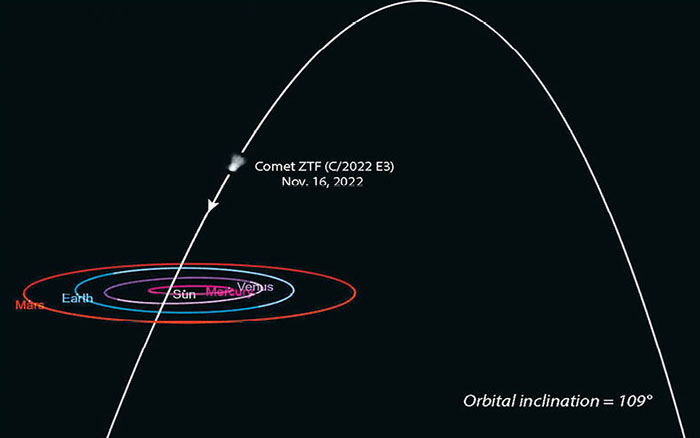

Comets follow widely different paths around the Sun with varying periodicities, large eccentricities and almost all possible inclinations to the ecliptic belt to which planets and satellites are confined.

Short-period comets generally have periodicities of up to a few hundred years. Halley’s comet is perhaps the most famous short-period comet, with a periodicity of about 76 years. In contrast, the comet of present interest appears to have a periodicity, if at all, of about 50 thousand years! This appears to be the main reason for its current popular fascination despite its difficult visibility.

Though comets are plentiful in the solar system, those that get close enough to become visible to the naked eye are quite rare. The last naked-eye comet was Hale-Bopp in 1997.

The 1965 comet Ikeya-Seki was a spectacular one and Halley’s comet of 1986 was a huge disappointment in relation to it. The expected increase in brightness of a comet as it approaches the Sun or the Earth is rarely predictable with any degree of reliability, much to the annoyance of most observers, both professional and amateur.

As we bid goodbye to the current comet of our curiosity, we hope these visitors from outer space continue to entertain us, and more frequently too, despite the popular fears and myths associated with their visitations.

![Goodbye, Comet C/2022 E3 [ZTF]](https://starofmysore.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Comet-C-2022-E3.jpg)

Recent Comments