By Girija Madhavan

Chanoyu,” or “The Way of Tea” is a Japanese tradition of serving tea, a ritual evolved over centuries. It is the ceremonial presentation of “Matcha” or powdered green tea by a Tea Master [man or woman] to a small group of guests, generally in specified tea houses. With Zen Buddhist origins, it celebrates aesthetics and harmony. As a teenager in the 1950s, I had heard of a Hollywood film, “The Teahouse of the August Moon.” Adapted from a novel by Vern Sneider, it starred actors Marlon Brando and Glen Ford. I do not remember having seen it in the Gayathri Theatre in Mysore which screened many English films.

Tea was brought to Japan from China in the 9th century and was first used in monasteries. By the 13th century, tea was considered an exotic drink and became a status symbol of the leisured class and the Samurai or warriors. The Tea Master, Sen No Rikyu [1522-1592], gave the ceremony philosophical and cultural content. He divested it of ostentation, creating small rustic tea houses and simple Raku pottery which is popular even now.

The doors to the tea houses were small so that everyone had to bend to enter, symbolically making them equal. It also made the Samurai remove their heavy weapons! Sen No Rikyu, who is still revered in Japan, was ordered by the Shogun [military commander] to commit suicide. So in his 70th year he wrote a farewell poem and committed “Seppuku,”suicide by disembowelment.

Ink sketch of a Tea House by Girija.

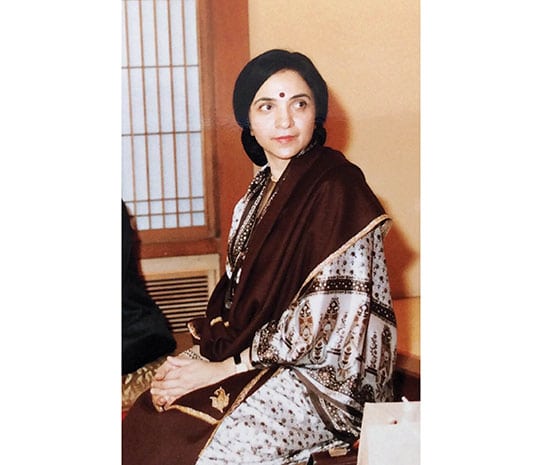

Tea Ceremony for Sonia Gandhi

My husband Madhavan was posted as Ambassador of India to Japan in 1985. In the autumn of that year Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, accompanied by Sonia Gandhi, made the first of his three visits to Japan. A Tea Ceremony was arranged for Sonia Gandhi and I accompanied her to it. With officials from the “Gaimushu” [Japanese Foreign Office] and translators, we walked through a charming garden to the tea house, leaving our footwear outside the tatami [straw mat] room. After an exchange of bows, we sat down in the customary kneeling position, ankles tucked under us. Mrs. Gandhi assumed the posture with ease and held it through the ceremony. But my ankles and knees began to ache badly and I had to change to a cross-legged position unobtrusively.

Formality is an inherent part of the ceremony. Every action of the host or hostess is akin to the choreographed movement of an elegant dance; from holding a serviette, mixing the tea powder and hot water with a whisk, pouring it in bowls and handing it to guests with a courteous bow. Many years are spent learning the gestures appropriate to the routine. The guests too are expected to make suitable moves; admire the decorations in the room like scroll paintings or flower arrangements and the tea bowls. They sip the mildly bitter green tea, turning the decoration on the tea bowl away from their lips. Though stylised and formal, the responses have an inherent grace and politeness. Host and guest, both have to focus on unhurried but studied actions.

Girija at the Tea Ceremony, 1985.

The seasons and months in Japan are associated with specific flowers, leaves or even grasses. Japanese art has many paintings featuring the birds and flowers of the Four Seasons. The brocaded kimonos of Japanese ladies may have symbols of the season woven into the design. Behind the host at the tea ceremony, a scroll featuring a motif suitable to the time of the year is usually hung; cherry blossoms in April or a painting of the red foliage of the Japanese maple in autumn. A small flower arrangement is placed in a suitable niche. The implements for the ceremony are set out; a brazier for hot water, a container with green tea powder, a bowl to mix it with the hot water, a whisk to make the mixture smooth and frothy; elegant ceramic bowls to serve it to the guests.

Attending this ceremony was possible for tourists to Japan or when Japanese Embassies abroad arranged special exhibitions. Now it is possible to view an authentic Tea Ceremony even in Bengaluru. Mme. Norie Ogha Manikath is a Japanese lady married to Krishna Kumar Manikath. They live in Bengaluru, often making trips to Japan. She has been my friend for over thirty-three years since we first met in Tokyo in the 1980s. She is a talented exponent of the Tea Ceremony. She taught me to sing the sweet Japanese song “Sakura, Sakura” about Cherry Blossoms in spring. Her father presented me a stamp with my name in Devanagari script and incorporating a small line drawing of Chamundi Hill. It is for me to stamp my ink paintings in the manner of Japanese artists and is a treasured possession.

A treasured possession.

In Japan, old traditions are cherished and maintained with care, ensuring their authentic continuation over the years. The Tea Ceremony is a celebration of aesthetics and a feeling for beauty. It symbolises the values of serenity, respect, purity and tranquillity.

Recent Comments