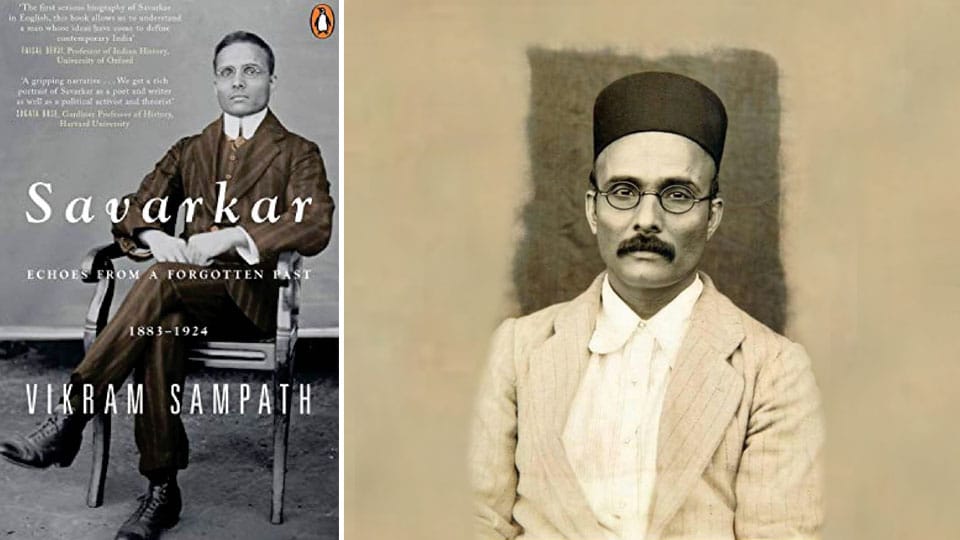

Title: Savarkar – Echoes from a Forgotten Past (1883-1924)

Author: Vikram Sampath

Pages: 735

Price : Rs. 799

Publisher: Penguin

By U.B. Acharya

Recently I attended a book release function at a well-known hotel in Mysuru. The release of the newly-published book, “Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past (1883-1924)” was organised by a local Book Club and it goes without saying that the hall was jam-packed with educated and well-read Mysureans. The young author Vikram Sampath was present and the chief guest was Tejasvi Surya, a bright and first-time MP of South Bengaluru Constituency.

I read this book from cover to cover in about a fortnight. This book is actually Volume I and is a detailed biography of a freedom fighter, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar up to his age of 40 years. The book is priced at Rs.799.

A summary of the book

Vinayak was born to Damodar Savarkar and Radha in 1883 at Bhagur in Maharashtra and the parents were fairly well to do financially. His elder brother was Ganesh (aka Baburao) and the younger brother was Bal. Radha died in 1893 and his father also died in 1899. He went to high school in Nasik and passed matriculation in 1901 with flying colours. The same year he married a 13-year-old Yamuna, daughter of Bhaurao Chiplonkar and later in January 1902, joined Fergusson College in Pune in Arts stream.

At Fergusson College he became passionate about Hinduism and freedom from the British rulers. This College had many past and present freedom fighters. In October 1905, he participated in the burning of the foreign clothes and it brought the attention of the British Police on him. Thus he was already a marked man by the British intelligence. In December 1905, he graduated with a B.A. degree.

In June 1906, he went to England with a UK scholarship plus his father-in-law’s money to study law. He was admitted to the Gray’s Inn and stayed at the India House. In those days, India House was a hotbed of Indian independence movement and some Britishers also sympathised with this cause. In addition, the civil liberties such as free expression of speech were much more relaxed in England than in India. However, even in London the British Police were keeping an eye on Savarkar because of his earlier activities in India and now in London.

In May 1907, the India House celebrated the Golden Jubilee anniversary of 1857 Sepoy Mutiny which young Vinayak termed as the “First War of Independence.” By 1909, Savarkar was in charge of India House and at that time, his only son died in India. Meanwhile, his brother Baburao was arrested for anti-British activity, tried and sentenced to life imprisonment to the Andaman Island (that is, Kala Pani).

Savarkar was arrested in London in 1910 for an attempted murder of a British Officer. Though he was not directly connected with this incident, the British Police wanted some reason to arrest him. When the Court could not find sufficient proof of his involvement, they extradited him to India for his misdeeds in India. His arguments that he was not charged with any crime while in India and therefore a free man, and could be tried in London for any misdeeds carried out only in that place did not carry any weight by the British Judge. He very well knew that punishment in UK would be considerably less severe than in India. Because of his arrest, he was not only thrown out of Gray’s Inn but also his B.A. degree was withdrawn!

When the ship had docked in Marseille Port, Savarkar managed to jump from the toilet’s small window and fell on the port’s pier. He ran to the nearest French security personnel and surrendering himself requested for political asylum. In theory, once he was in French soil, he was under French jurisdiction. Meanwhile, the British Policemen realising his escape came chasing and found him with the French security personnel. He, without checking with higher authorities, meekly handed over Savarkar back to British Police!

Savarkar was tried in an Indian Court and was found guilty of treason against the British Raj and sentenced to two consecutive life imprisonments (a total of 50 years) in a cellular jail at the Andaman Islands from June 1911. In the jail, he was put in total isolation and given hard labour of husking coconuts and extracting oil of certain minimum quantity. He was also made to work as a labourer in the farms. The food was not eatable and he was denied any reading or writing materials. He was not allowed to meet his brother who was also serving sentence in the same prison. His health deteriorated very badly.

When the durbar of the then King and Queen of England was held in Delhi in December 1911, some release and redemption of the jail terms were carried out but not to Savarkar or to his brother Baburao. Meanwhile, with some papers he got from the prison authorities, he wrote petitions to the Viceroy of India requesting release of all prisoners. (In later years left leaning Indian historians have concluded that he chickened out and became subservient to the British Raj. This is a complete distortion of the true story).

During the First World War (1914-1918), Indian political leaders stopped their independence agitation and actively helped the British with a hope of getting some major concessions like the home rule and release of all prisoners. While a very lukewarm concession was given to India and following Savarkar’s one more petition, some prisoners were released but not him. His petition to allow his wife to travel to the Andaman Islands for conjugal rights which was permitted as per the British law was also denied.

During his India House days (1906-1910) in London, he had formulated his philosophy of “Hindutva” but had not put it in writing. Later at the cellular jail as he was not given any writing materials, he started writing it in the prison wall with stones! He memorised them and finally managed to write on paper given by other prisoners and managed to smuggle it to India through prisoners who were released between 1917 and 1919. The book “Hindutva” was published later in 1923 or so when he was still in Indian prison.

In May 1921, he was transferred from the cellular jail to Ratnagiri prison. At Andaman because of his good conduct, he had eventually obtained some privileges but all those were denied to him at Ratnagiri. The condition of the jail was indeed very bad. Subsequently in 1923, he was transferred to the Yerwada prison where M.K. Gandhi was also imprisoned for civil disobedience. As their ideologies were different, there was no rapport between the two.

Finally on 6th June 1924, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was released from the Yerwada jail under the condition that he would not indulge in any political activity and that he would confine himself only to Ratnagiri District. Thus he spent in jail from 10.3.1910 to 6.6.1924 from London to India to Andaman Island and back to Indian prison. The book (Volume I) ends with his release from the Yerwada prison in 1924.

Review of the book

The book has been written in a very simple language, unlike the high sounding writings of Shashi Tharoor. The author has taken a lot of pain in carrying out extensive research by spending a couple of years each in Delhi digging written materials from the Government’s files as well as in London’s foreign office archives. The detail with which the author has narrated the life history clearly shows efforts he has put in writing this book. He has even travelled to Port Blair and visited the Kala Pani jail.

The book has some 200-plus pages of appendices and notes. Copies of Savarkar’s petitions, arguments in the Courts as well as the judgements are either reproduced in total or its references available in various archives have been included. Thus it is an exhaustive and painstaking compilation.

Though some readers of this book have commented that they read the book in three days, I must admit that this book is not everyone’s cup of tea. One has to be interested in 20th Century Indian political history and more importantly, definitely leaning towards “rightist” attitude. One sentence of the author really attracted my attention. It reads, “Savarkar and his views could not have been more relevant to Indian politics now, in 2019 with Indian ‘Right’ being in the political ascendency.” With 60-plus years of India’s ‘Left’ leaning Governments, Savarkar has been thrown into the dustbin. The author has attempted to correct this misconception.

Though not written in this book, the author says in some other writings that when he went to School and College, there was no mention of Savarkar in text books. When plaque (installed by Vajpayee Government in the cellular jail) controversy took place in 2003-2004 between BJP and Congress, it roused the author’s interest in Savarkar and he decided to investigate further. It is a historian’s job to make the facts available to the discerning readers so that they can make up their own mind. The book does not idolise Savarkar or demonise him (like A.G. Noorani).

Should he submit this book as a thesis for doctorate to any well-known University in USA, UK or India, he is certain to get a second Ph.D. in modern history.

About the author

Dr. Vikram Sampath is a Bengaluru-based author and historian. He has three degrees (BE, M.Sc., and MBA) from Birla Institute of Technology, Pilani in Electronics, Mathematics and Finance. He also has a MBA degree from S.P. Jain Institute of Management. In addition, in 2017 he obtained a Ph.D. from University of Queensland, Brisbane in Music. He is an excellent singer of Karnatak music. He is a Visiting Professor of that University. He is proficient in English, Kannada and Hindi, and has working knowledge of Tamil, Marathi and German.

He has a couple of books to his credit. He is now working on Volume II of Savarkar’s biography which is expected to be published in two years time.

Recent Comments