By Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik – Author, Speaker, Illustrator, Mythologist

The two ideas may shape our understanding of conflicts, but Hinduism, which is based on karma, is more complex. Whenever we are deeply hurt, a question comes to our mind: do we seek justice through retribution, or do we let go? Justice and forgiveness are two concepts that really come to us from the Bible. In the Judeo-Christian-Islamic framework based on Abrahamic mythology, God is the judge. The Old Testament speaks of ‘an eye for an eye’, which is about justice and vengeance. The New Testament speaks about ‘turning the other cheek’, if slapped on one, which basically refers to forgiveness. These two ideas shape our global understanding of any conflict. People have tried to use the same framework to appreciate the Hindu response to a crisis. Therefore, when there is a crisis, people need either justice or a compromise for peace. The Hindu worldview is more complex than that. Hinduism is based on karma: every event that happens before us, or to us, is the result of the seeds we sowed in the past. Hence, we must take responsibility for events which happen in our lives. Taking responsibility, however, is the toughest thing in the world. It’s very difficult to handle.

Let’s understand karma by looking at the epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. The Ramayana begins with the story of Valmiki watching two birds, one of whom is shot and killed. The surviving bird mourns the death of her beloved. Valmiki gets so upset by this event that he curses the hunter. The bird cannot curse, it only knows how to grieve. This event draws attention to the difference between animals and humans, nature and culture. In nature, there is no concept of justice or forgiveness, there is only suffering. Humans, however, can compensate for suffering by demanding justice or forgiveness. Or maybe there is something else because the human mind is capable of imagining a world of karma where every event occurs because it’s supposed to occur: there is no one to blame and therefore, no one to forgive.

When Rama kills the monkey king, Vali, and the demon king, Ravana, their wives are devastated. In many retellings, Vali’s widow, Tara, and Ravana’s widow, Mandodari, curse Rama that he will also face separation from his spouse. This has been cited as the reason for Sita’s banishment from Ayodhya. Rama pays the price for his military victory, however righteous his war may or may not have been. He does not complain about it.

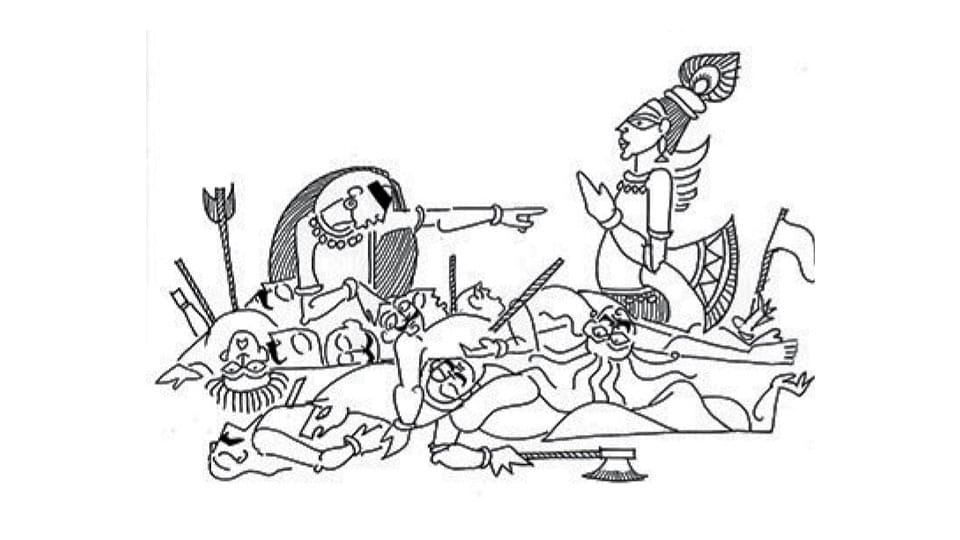

Likewise, in the Mahabharata, everybody speaks of how Krishna establishes dharma by getting the Pandavas to defeat the Kauravas. However, we rarely speak about the collateral damage: the death of Draupadi’s children, Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu and Bhima’s son Ghatothkach; how Gandhari curses Krishna and his entire clan is wiped out eventually. Krishna does not complain. Even a dharmic war has collateral damage, which Gods accept without getting upset. Consequences are a part of life.

This worldview is very different from the outlook which demands justice or forgiveness. In the world of Rama and Krishna, every action has a reaction. One learns that negative events in our lives are the outcome of our past actions. If we respond to these events, we sow fresh seeds, which lead to positive or negative outcomes. The seed and the fruit follow each other unless we step back and witness life, as sages and Gods do. We often discuss how Krishna established dharma by getting Pandavas to defeat Kauravas, but we rarely speak about the collateral damage.

If it is what it is, actions leading to consequences, why does Krishna or why do we interfere in the natural cycle of the civilization? If Ravana, or the Kauravas acquired bad karma in their life, would they not pay for it in their future life? What was the need for Krishna to interfere then?