By Gouri Satya, Sr. Journalist

In my previous article on the De Havilland Arch of Srirangapatna (Star of Mysore dated Dec. 20, 2020), I had mentioned about this engineer’s association with the 1810 mutiny in protest against the appalling conditions of the Army in Mysore, resulting in his dismissal from service and subsequent reinstatement in 1812. Readers of this article might have wondered what this mutiny is all about where a British engineer was associated with and what were the appalling conditions.

Mutiny of the Army in Mysore

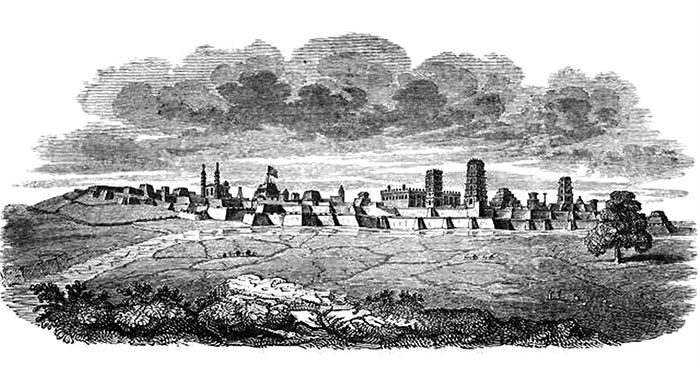

Last year, I wrote an article on this mutiny in a national newspaper under the title ‘The Bloody Great White Mutiny’, where I had written about the historic revolt at Srirangapatna which resulted in dismissal of several British army men and ghastly death of several hundred sepoys in the ditches of Srirangapatna.

This mutiny has great significance because it was a revolt by the British sepoys against their superior officers. They disobeyed the orders of their officers and marched to the capital to lay siege. It was a mutiny not only in and around Srirangapatna but even in other parts of the country.

If it had escalated further, it would have had the serious effect of toppling the very British rule in India. However, it was crushed before it could blow up further. What would have been a major threat to the British rule in India fizzled out because of the ruthless hand with which it was put down.

In the colonial history of India, perhaps this is the only revolt by the British sepoys against their superiors. May be because of this reason, this revolt did not receive the importance it should have got by the then historians who were recording the history of that period. However, it is a significant incident in the British history of India.

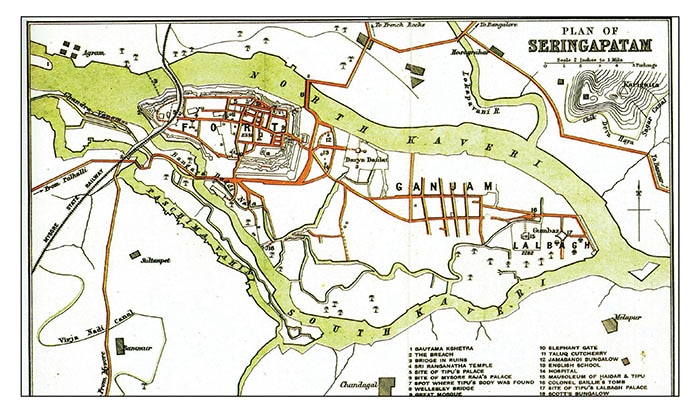

A revolt soon after IV Mysore War

Another significant aspect of this revolt was that it arose just a decade after the defeat and death of Tipu Sultan and the resultant fall of Srirangapatna in the 1799 Fourth Mysore War. The revolt plunged the entire South India in turmoil for three months. It covered a wide area of three strategic forts — Machilipatnam, Hyderabad and Srirangapatna. The origin of this major outburst was not Srirangapatna, but the headquarters of the then Madras Presidency, Madras. It was a protest against the highest British authority of South India — the Governor of Madras.

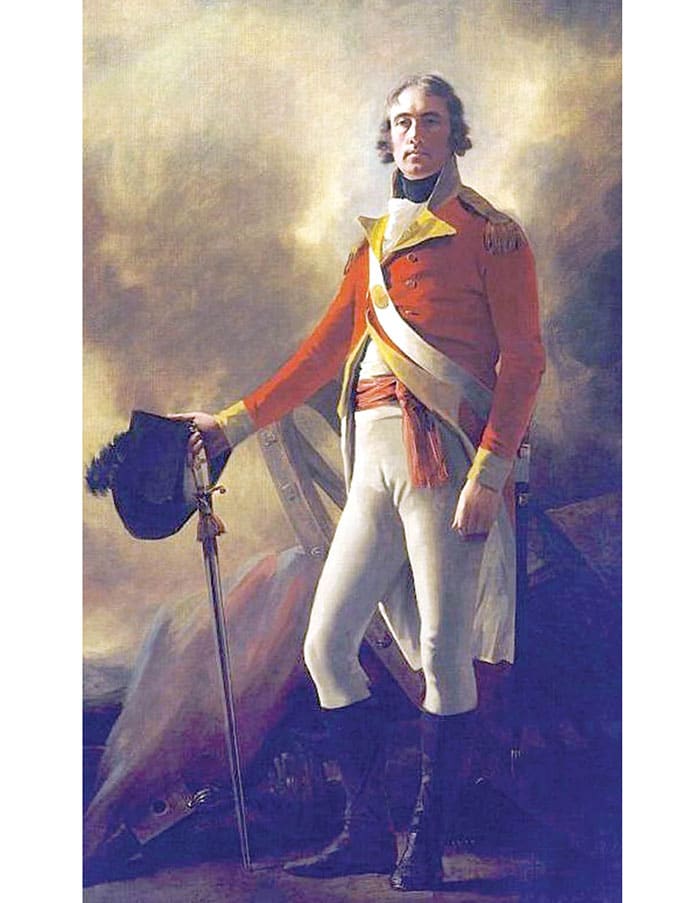

Trouble began to brew soon after the appointment of George Barlow as the Governor of Madras in 1807. After his appointment, George Barlow took some actions in the name of economy which were resented by many in the Army, including the Madras officers. Suspending officers without trial and seizing the powers of the Commander-in-Chief at Fort St. George further aggravated the situation. It affected discipline in the army and gave room for discontent.

Room for discontent

Two particular issues caused great dissatisfaction among the juniors in the Madras army. One was not complying with the demand for equalisation of allowance in Madras on par with Bengal and the other was abolition of the rent allowance granted to commanding officers.

The previous Governor and the Commander-in-Chief of Madras had recommended equalisation of allowance in Madras on par with the officers of Bengal, where it was higher, and abolition of the tent allowance which was granted to commanding officers of regiments in 1802.

These recommendations were, however, ignored by Barlow. Tent allowance provided the officers in command of regiments with a fixed monthly allowance for transport and camp equipage. Now, they had to forego this allowance.

Lack of representation

Another major blow by the Governor was leaving out the Commander-in-Chief from the Council. This action deprived the officers of a representative in the Council Board to air their grievances. These repulsive actions of Barlow were resented by the army men, including some officers of Madras.

Commander-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Hay McDowall gave an impetus to the revolt. His disenchantment with Government was because of the decision to deny him a seat in the Madras Council, a position accorded to every previous commander of the Madras army. Upset over this, the Commander-in-Chief committed ‘open sedition and sent forth an inflammatory appeal from the acts of Government.’

Initially, trouble arose at Cochin. But, it was put down by Barlow. However, it cost 140 lives. Then the first act of open defiance came from the Company’s European regiment in the garrisons of Machilipatnam in May 1809. Two dozen European officers seized the fort and arrested the commanding officer. They over-powered the guards of the treasury and took away whatever they found inside. This was followed by a similar mutiny at Srirangapatna, while the officers of Hyderabad threatened to march to Madras to seize the Government.

Mutiny spreads

The mutiny led by officers spread soon threatening the entire British position in India. In some of military stations rebellion against their Government in Madras and elsewhere resulted in widespread violence. There was suspension and removal of the rebellious men and officers from their posts, posting of new ones in their place, seeking expression of loyalty to the Government and awarding such men during this period. These actions led to further large-scale protests by the Army men at several places.

Ninety percent of the 1,300 officers commanding the native force refused to obey the orders of their superiors. Only 150 senior officers signed the test of loyalty Barlow had imposed. The rest locked up their colonies, broke open the treasury and took out thousands of pagodas to pay the native troops whom they had managed to keep under their control. For three months from beginning of July to the middle of September 1809, there was lawlessness in the whole of Southern India.

Revolt at Srirangapatna

The revolt by the troops stationed at Srirangapatna under the influence of Col. John Bell of the Company’s Madras Artillery, who had been court-martialled in Bangalore, was of a serious nature. There was large scale violence and defiance of the Commandant of the Division. Rebellious attitude by European officers besides the natives was witnessed throughout the greater part of the Army.

Systematic aggression and insubordination were seen all over. Self-constituted committees usurped the military authority entrusted to the commanding officers and seized the garrison. Col. Bell, who was in command at Srirangapatna, defied the Commandant of the division, seized the treasure in the Fort.

During July-end, the Chitradurga troops seized the public treasury and deserted their posts. Two native battalions marched from Chitradurga to join the rebellious troops at Srirangapatna on August 6. En-route, the troops plundered villages.

Protecting property

Apprehending that the valuable property of the Maharaja and the Dewan, which “amounts to be a considerable sum”, may become target of the rebels, guards were placed in the Fort over the personal property of Krishnaraja Wadiyar III and Dewan Poornaiah in Srirangapatna.

Meanwhile, the British army continued to put down the aggression. While on the march to Srirangapatna, two battalions of Chitradurga were attacked by a body of Mysurean Horse and the 25th Dragoons, which had been collected by the Resident to intercept the Chitradurga rebellions. In the operation, as many as 550 men were either killed, wounded or went missing. However, rest of the British and native officers and about 800 men made their way to Srirangapatna.

Resisting the mutiny

In the meantime, the Government had mobilised a large force to resist the mutineers. The mutineers opened fire upon the forces protecting the Fort and made a few sallies. Under the command of Lt. Col. Gibbs, a detachment from the British force defeated and dispersed the rebellious troops from entering into the Srirangapatna garrison.

The defeat of the rebelled troops and their surrender was achieved under the direction of Arthur Cole, Senior Assistant to the Resident, in Mysore on August 23. The Great White Mutiny came to an inglorious end, but saw several hundred sepoys lay dead in the ditches of the capital. The mutineers were court-martialled and dismissed from service.

Cole was rewarded with Acting Resident’s post and subsequently the Resident’s post because of “his prudence, wisdom and fearlessness, contribution very essentially to the restoration of order and the prevention of sanguinary extremities” during the mutiny of the British officers of the Madras army in 1809. It was in this mutiny De Havilland had taken part but subsequently apologised to be reinstated.

Your piece was very revealing. I had never heard about, ‘Great British Mutiny’. Thanks for sharing.