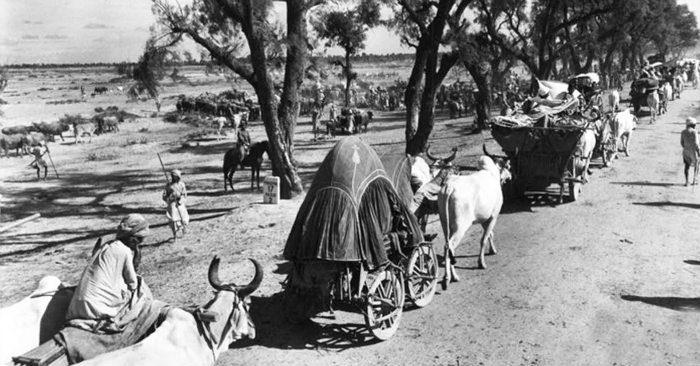

This is the 70th year of India’s Independence. Every time we recall the ‘Tryst With Destiny’ speech by the first Prime Minister of the country Jawaharlal Nehru in India’s Constituent Assembly, we also recall that outside the well-guarded enclaves of New Delhi the horror of Partition was well underway.

Twenty years ago when the country celebrated its Golden Jubilee of Independence, Star of Mysore had written about “Trauma of Partition Recalled,” in its ‘Golden Jubilee of Indian Independence Special Issue’ dated August 14, 1997. SOM had spoken to three people, who immigrated to India after Partition — J.C. Gupta, the then Director of Glowtronics, K.L. Passi, a Class A Contractor and J.R. Sharma, CFTRI Scientist, who had all settled down in Mysuru after Partition. Now, twenty years later, there are very few people living to share the agony of those days. Hence, SOM decided to meet the post-Independence people coming from what is now Pakistan.

Star of Mysore Features Editor N. Niranjan Nikam spoke to Kamal Kant Bagai, Anthropologist and former Head of Office, Anthropological Survey of India, Southern Regional Centre, Mysuru; Prof. Rajesh Sachdeva, former Director, Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL); Prof. Mewa Singh, Life-Long Distinguished Professor, University of Mysore and Dr. Hansraj Dua, former Professor in CIIL. The common thread that ran through the conversations between the four —“The Partition brought both the sides (India and Pakistan) misery, sorrow and violence. Instead, why can’t we dream of an Akhand Bharat at least now?” —Editor

By N. Niranjan Nikam

Only three communities bore the brunt of Partition — the Punjabis, Sindhis and Bengalis. Even the Kashmiris did not feel the bitterness, violence, being uprooted, removed from their land like these three communities. Of course, Indian Muslims from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh and other places did bear the brunt, said Prof. Rajesh Sachdeva, recalling the horrors of Partition.

“I was born after Partition. But my parents came as refugees to Delhi. My grandfather was a respected school teacher in Gujranwala, now in Pakistan. Everybody spoke and wrote Urdu. My father did his schooling in Urdu. And I have heard the experiential account of my parents of Partition as a child, which sets me thinking always, what if it had not happened?” said Prof. Sachdeva.

Prof. Hansraj Dua, who was the only one among the four who witnessed the Partition, reminisced about those days when he was a child of around 12. “I was living in a small village, Chak 38, near Mandi Bahauddin, in what is now Pakistan. There were very few Hindu families and it had a majority Muslim population. Everyone was living in total harmony. Suddenly there was talk of Partition. We were asked to shout slogans like Pakistan Zindabad. Then we did not think that we would be moving out. Because we did not know what the world outside was,” recalled the octogenarian Prof. Dua.

Then the dreaded thing happened. You are Hindus; you have to move out of this village. The stories of communal violence and civil war started penetrating. The family was first moved to a nearby urban centre and lodged in a government school premises. It was a camp but it could still not be called a refugee camp.

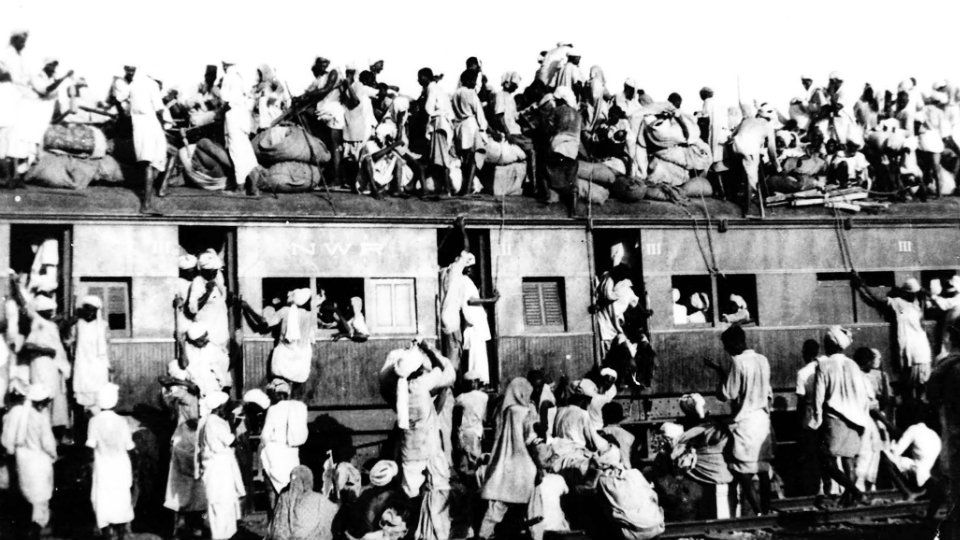

“The sanitation condition was very poor. There was an outbreak of cholera. People all around were dying. There was a sense of bitterness, sorrow and regret even as the stench of dead bodies kept hitting us. Finally, the army came and we were relieved. We were all put on a goods train and it took us three days to reach Amritsar as the train would halt for hours,” he said and added, “We also had the fear that the train would be burnt. And when we arrived in Amritsar we were given food. From there we moved to Rajasthan and now I have retired in Mysuru,” said Prof. Dua with a great tinge of sadness, anguish, sorrow and relief.

Prof. Hansraj Dua

“My mother Janak Lata Bagai wanted to be a dentist. But, when a teacher in a college in Gujranwala, where she was born, eloped with his student, it put an end to her studies. Her father took her out of school and taught her Urdu because it was a beautiful language of India,” said Kamal Kant Bagai.

“We are impoverished as far as language is concerned today. We neither have the verbal repertoire nor can we articulate the way our forefathers did,” said Prof. Sachdeva, the Linguist.

“She would wrap around a khadi-woven saree as a young girl and along with other girls wave flags, picket in front of liquor shops and break bottles. She had heard of Gandhiji and Subash Chandra Bose,” said Bagai.

Kamal Kant Bagai (left) and Prof. Rajesh Sachdeva

In the undivided Punjab of those days Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims all spoke Punjabi. The word Sikh means learning, a Shishya. The Sikhs never believed in caste or man-made boundaries. Everybody sported a beard and a turban those days and it was not just confined to the Sikhs, reminisced Bagai and Prof. Sachdeva.

“My mother Vimala Sachdeva was a graduate and a gold medallist in Sanskrit. She knew Urdu and Punjabi and her best friend was a Muslim. My father Yogaraj Sachdeva was in the army,” said Prof. Sachdeva.

His (Sachdeva) mother narrated the story of how they had to leave Pakistan. They were living in a comfortable house with all facilities. His father was at work. His mother was cooking. Suddenly a person came from the army and asked her to immediately leave. She just picked her two daughters, a few items and left behind silver, crockery and reached Dhaepai, near Amritsar to her husband’s elder brother’s place. “It was the height of civil war. My mother did not know anything, but a few days later she learnt what my grandmother living in Ferozepur had done. Even as hordes of Hindus came shouting Har Har Mahadev to their house and threatened my grandmother suspecting that she was hiding Muslims in her house, she would fiercely protest and ask them to go away. She had hid nine Muslim families in the basement!,” said Prof. Sachdeva and added, “The very next train, after the one that had carried my mother and sisters, was completely burnt.”

Recalling his father’s experience, he said that his father’s boss was a Muslim and so was his clerk. He had to remain in Jhelum for about two months. Finally, one day, the clerk told his father that the boss was turning against him. “Aaj raat aap gaadi se nikhal jayie.” And he left without telling his boss. He had grown a beard and almost looked like a Pathan. Those were the days of uncertainty. Finally, the train reached Delhi and, “As you see in the movie Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, the administration had set up camps and because the documentation was so good, my father traced my mother’s family. My mother could not recognise him immediately,” said Prof. Sachdeva.

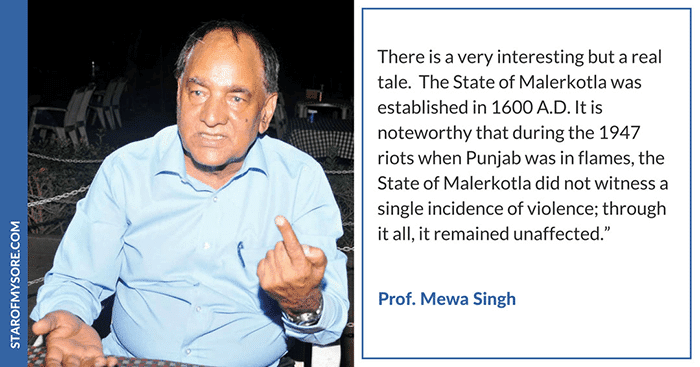

Malerkotla, lone island of peace

Prof. Mewa Singh, listening to the stories of Partition and its horrors, quietly told this writer in a very measured voice, “There was not a single Muslim killed during Partition in Malerkotla, where I was born.” When asked him for the reason, he said: “There is a very interesting but a real tale. The State of Malerkotla was established in 1600 A.D. It is noteworthy that during the 1947 riots when Punjab was in flames, the State of Malerkotla did not witness a single incidence of violence; through it all, it remained unaffected.”

The roots of communal harmony date back to 1705, when Sahibzada Fateh Singh and Sahibzada Zorawar Singh, 9 and 7-year-old sons of 10th Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, were ordered to be bricked alive by the Governor of Sirhind, Wazir Khan. His close relative, Sher Mohammed Khan, Nawab of Malerkotla, who was present in the court, lodged vehement protest against this inhuman act and said it is against the glorious tenets of Quran and Islam.

However, Wazir Khan did not heed to the protest. He had asked the two young sons of Guru Gobind Singh to convert to Islam. The children refused. Wazir Khan had them tortured and built a wall around them, while they were still alive. When they did not heed to his demand for conversion, Wazir Khan beheaded both of them, narrated Prof. Mewa Singh.

When Guru Gobind Singh learnt about the protest made by Nawab for the killing of his two sons, Guru Gobind Singh blessed the Nawab with his Hukamnama, Kirpan, etc. In recognition of this act, the State of Malerkotla did not witness a single incidence of violence during Partition.

But Guru Gobind Singh’s disciple Banda Singh Bahadur went to Sirhind and killed Wazir Khan thus taking revenge for his Guru’s sons’ inhuman killings, recalled Prof. Mewa Singh.

Reciting the lines of Amritha Preetham, the renowned Punjabi poet’s Ajj Aakhan Waris Sha Nu, a famous dirge about the horrors of the Partition of Punjab during the 1947 Partition of India, he said, the poem is addressed to the historic Punjabi poet Waris Shah (1722-1798), who had written the most popular version of the Punjabi love tragedy, Heer Ranjha.

Amritha Preetham

Today, I call Waris Shah, “Speak from your grave,”

And turn to the next page in your book of love,

Once, a daughter of Punjab cried and you wrote an entire saga,

Today, a million daughters cry out to you, Waris Shah,

Rise! O’ narrator of the grieving! Look at your Punjab,

Today, fields are lined with corpses, and blood fills the Chenab.

“One of my elder brothers, a farmer, who works in the fields, always sings the song of Heer Ranjha while driving his tractor. There are also many research works on this famous poem,” said Prof. Mewa Singh.

“We should nurture the idea of India, the cradle of world civilisation, as Akhand Bharat. Let us get back to the old days before the Partition. India without borders, both within and without, is the only way forward. When East and West Germany could be united, why cannot we think of something similar? Until today, we are paying a price for Partition. You cannot redraw the border but you can make them irrelevant,” was the unanimous voice and call of all the four Punjabis, whom this writer spoke to.

Recent Comments