By P.K. Misra

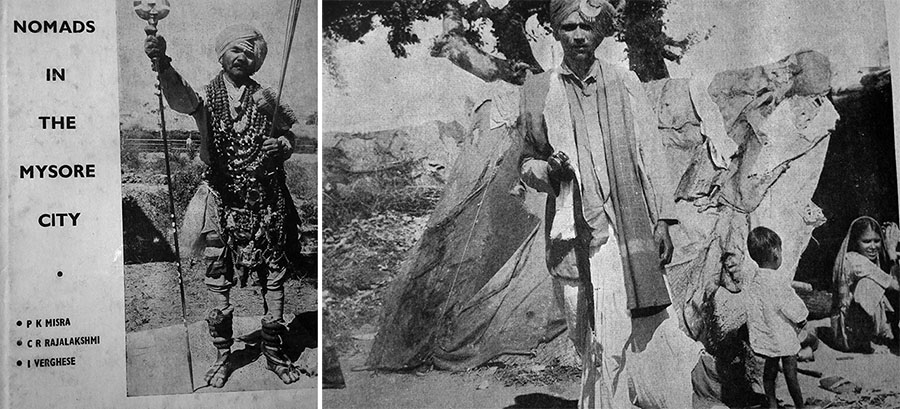

[Pics. courtesy: IGRMS- Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalya]

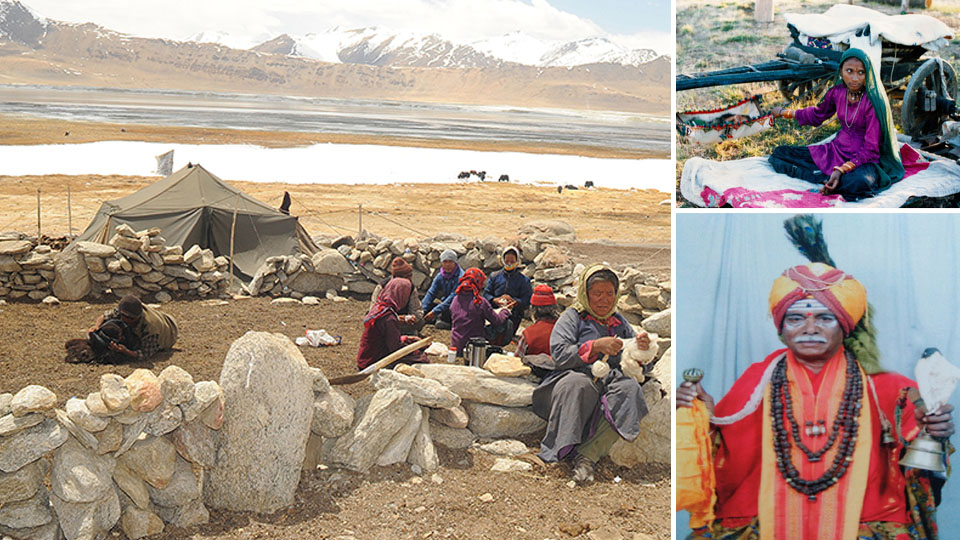

India is home to millions of nomads who belong to hundreds of distinctive groups. Unfortunately, most nomadic communities are witnessing a breakdown in traditional modes of living. Mysuru’s Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya is presently organising a year-long exhibition on ‘Nomads of India’ at Wellington House, Irwin Road. To coincide with the exhibition, in this Weekend Star Supplement, we publish an article on India’s vanishing nomads — caught between tradition and modernity.

Nomads on the Face of Fading Tradition

One of the qualities human beings developed in the course of their evolution is to move out of their habitats for a variety of reasons such as economic compulsions and ecological factors. But what is not highlighted is the human spirit expressed in their intense sense of curiosity to explore and their indulgence in adventure and discovery.

This spirit enabled human beings to colonise almost all corners of this planet despite numerous challenges. And now the same spirit is taking human beings to establish space stations. Here I intend to talk about those who habitually move from one place to another at regular intervals focused around certain centres of operations. They are Nomads.

A life of fascination

Nomadic way of life is fascinating on its own right but it certainly puts forward an alternative vision of life. Their life from standards of settled people may look tough and rugged but wait just before you pass judgment. The intricate and beautiful designs they make on daily use items speak volumes about their patience and creative abilities – in short, the celebration of life.

Nomads could be of various types such as food gatherers and hunters called foragers (it may surprise many people to learn that a few decades ago, just 45 miles away from Mysore there were classical food gatherers like the Jenu Kuruba), pastoralist (those who carry food on hoofs) who move to find suitable grazing grounds for their cattle and those who supply goods and services to the settled populations.

Latter people have been called by different names such as non-pastoral nomads, service nomads, and now more acceptable term for them is peripatetics. Unlike other nomads, they exploit the human niche. Peripatetics have been an essential part of Indian social organisation.

Fulfilling demand and supply needs

The traditional India was so constituted that villages were inhabited by peasants and numerous other communities specialising in a variety of occupations. What was not available in the villages was obtained from weekly markets, regional and mega fairs and also from pilgrimage. Whatever gap still remained in the supply of goods and services was provided by the other nomad foragers as well as peripatetics.

Pre-historical, historical and classical literature have indicated the countless generation of rural, urban and pastoral populations have experienced brief but usually recurrent contact with spatially mobile people indulging in a variety of occupations. These people relied on their flexibility and resourcefulness. They complimented the supply chain of rural areas.

Pervasive and persistent presence

Judicious combinations of specialised goods and services and skills, spatially mobile people of smiths, basket and toy makers, jewellery peddlers, recorder of genealogies and a variety of entertainers such as bards, bahrupia, jugglers, acrobats, singers and dancers etc., have been pervasive and persistent thread throughout the complex and immensely diverse fabric of India’s social system.

They are found all over more particularly in Asian countries. They have been mentioned in ancient Indian literature as people who travelled through towns and villages and served the common people. Though they have persisted throughout the history there is very little knowledge about them. The lack of knowledge and a certain ‘suspicion’ about mobile people led the dominant sedentary people to frame laws against their moving, camping and so on.

Multi–resource economic activities

During the colonial period many of them were declared as criminal tribe which was indeed a great injustice. In spite of such pressures, peripatetics have persisted through time in the different parts of the sub-continent.

Obviously the question arises as to what makes them tick. They have several qualities such as they spot the gaps in the supply of goods and services, their multi–resource economic activities compliment rather than compete with established system. Travelling is a condition of their livelihood, but its duration, frequency and mode has a lot of variety. They are generally multilingual.

The movement of the peripatetics is well directed. The remarkable thing about them is that in spite of the fact that they remain dispersed for good part of the year they retain their group identity. They have a home base to which they periodically return where they settle outstanding disputes among themselves.

Strong caste roots

Their caste council remains very strong the most interesting aspect of peripatetics in India is that some of them exclusively serve only certain castes which conclusively suggest that they are enmeshed in the socio-cultural profile and provide an important clue to understand India’s social structure. Studies conducted in 60s and 70s showed that villages were visited by scores of travelling specialists. In 1967 when I took a quick survey of certain parts of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, I met 40 different groups at different places in about fortnight’s time. These people camped beneath a tree, under a cloth tent, temporary huts or under the sky.

Travel specialists

They transported their baggage on the back of horses, donkeys, bullocks, or used bullock carts, trains buses or simply as head-loads. They indulged in a variety of occupations. They recited mythological stories, displayed sacred bulls and performed Ram Sita marriages (in local dialect, idiom and puns) and a variety of such activities which made appeal to the rural folks.

I came to know about 88 different peripatetic groups visiting their villages. In another study that we conducted in 1972 at the weekly market at Tarikere, we came across 200 different groups visiting the weekly market. But our information about them has been very scanty.

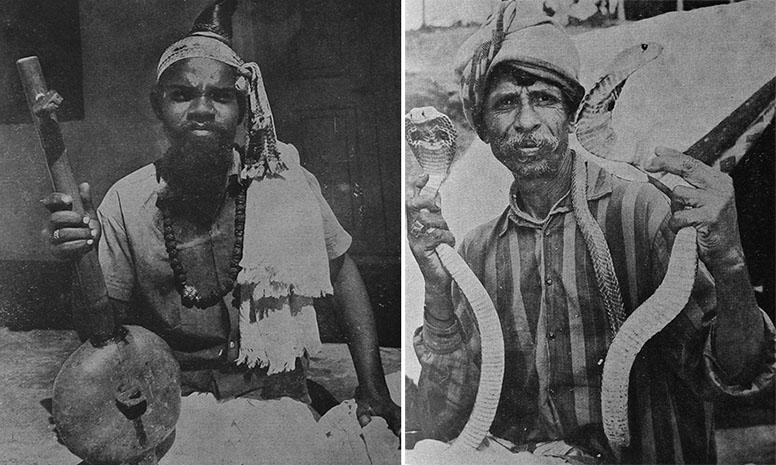

The stories of a Budbudki, Sudugadu Siddha, display of sacred bull or acrobats or displayer of leather puppets found a few decades ago in Mysore city may look anchoritic but imagine most of the city localities were known by the occupational specialist who lived there (See Gouri Satya’s article on Mohallas and Agraharas and Keris (Star of Mysore, December 3). It says everything what has been happening to this city.

Conflict between tradition and modernity has always been there but whatever is happening now seems to be qualitatively different. It is becoming more atomised and less integrated, and certainly harsh who nurture an alternate vision of life. Certainly there is very little room left for nomads — foragers, pastoralists or peripatetics and much less appreciation of what they did.

Nomads in Mysore

Nomads in Mysore city may sound so strange but in 1969-70 when we conducted a study on them we came across 19 different groups in a short span of time. At that time there were five different places where they usually camped at open spaces near Paduvarahalli, open space close to Mysore Railway Station, Jeevarayana Katte Ground, Kyathamaranahalli and open space near Mysore Railway Workshop.

The occupational roles these peripatetics performed enabled them to earn their livelihood but there is much more than that which cannot fully be understood without taking into account their cultural ethos. In this regard the role performed by Budbudki or the Sudugadu Siddha is illustrative and I quote from our book ‘Nomads in Mysore City’ (1971).

Sudugadu Siddha

A Sudugadu Siddha wears orange colour full-sleeved shirt and a dhoti also of the same colour. He receives one set of this dress free from the Jengudu Siddappaji Mutt in Arsikere taluk, during Shivarathri festival. The mutt prescribes to these followers of Siddappaji that they should wear this dress whenever they perform Jatra.

The mutt also gives each of them a short peacock feather bunch, a brass bell, a thin long bamboo staff and an umbrella to be carried along. Besides these a Sudugadu Siddha wears a lingam and several strands of Rudrakshi around his neck and a turban of a saffron cloth.

He smears ash over his face, keeps vermilion mark in the middle of his forehead and ties his matted hairs into a knot at the top of his head. The way a Sudugadu Siddha dresses himself and the pains he takes to remain standing on the nails for hours together cannot be explained just in economic terms.

In this attire he stands at a centrally located place on iron spikes fitted to wooden slippers. He stands still like a statue. His attire and posture are an attempt to imitate an ascetic engaged in tapasya. People offer money to him at his feet.

About the author

Prof. P.K. Misra is a retired professor of Anthropology and has served the country under various capacities. His last stint was at North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU) in Shillong. An authoritative voice in Anthropology, he is presently the President of Anthropological Association of Mysuru.

Thanks Dr Mishra for mentioning my article. I am happy it was useful for referring.

Gouri Satya (Your old French class colleague of Samachar!)