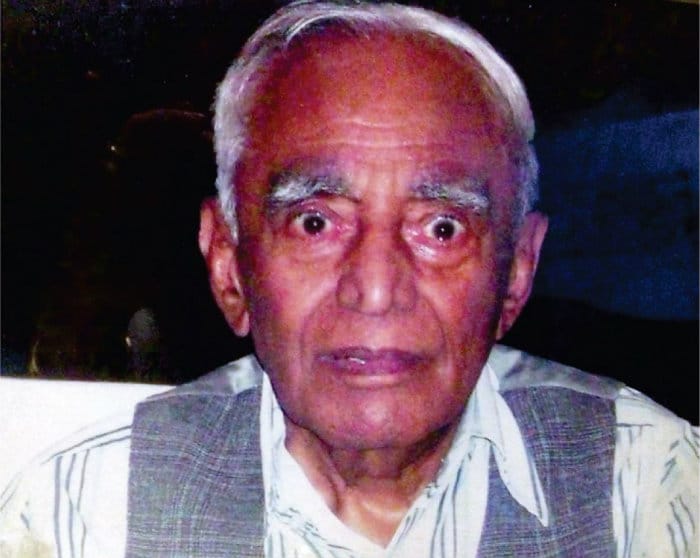

There are people who crave for publicity at the drop of a hat. There are a few others who go about quietly making a mark in the society and who shun it. To this noble league belonged former UN Diplomat Dr. Keshap Chander Sen. He had come from the US and settled down in Mysuru. He believed in social causes and ran a small organisation, which he called Lost Cause-Mini Fund. Dr. Sen funded this organisation himself and every year during winter, he would distribute free woollen blankets to the poor on city streets. He would drive around in the night, place the blankets on the people sleeping on the pavements and quietly move away.

Dr. Keshap Chander Sen

Dr. Sen passed away in 2008 in Mysuru. His son Atul Keshap, US Ambassador to Sri Lanka and Maldives, recalls his mother Zoe Calvert and father Dr. K.C. Sen’s India connection, the Partition and the US-India relations in this moving article on India attaining 70 years of Independence.— Editor

By Atul Keshap

It is just past midnight, Indian Standard Time, as I write these words. As August 15 begins, 1.25 billion of her citizens are marking 70 years since India’s Independence. Despite the tragic mess colonial functionaries created at Partition, a nascent Independent India generously gave shelter and comfort to my father, a penniless refugee, and granted him permission to continue his interrupted studies at the Delhi School of Economics, leading to his position in the Punjab Civil Service, a precursor to his United Nations career.

By a lovely quirk of history, my American and my Indian grandfathers were both born in undivided India. My youngest daughter was born in India. My Mother Zoë Calvert’s first assignment in the US Foreign Service was in India. Karen and I were privileged to serve in India as US Foreign Service Officers (FSOs) at a crucial turning point in bilateral relations. My elder brothers attended boarding school in the sacred Himalayan foothills of India. My father was born an Indian, became an American late in life, and passed away not in the undivided India of his birth, but nonetheless in the country and civilisation of his ancestors.

My first memory of visiting India is more than four decades old, of sleeping as a toddler on a charpoy, on a roof, at my grandfather’s house in a small North Indian town. Over the years, I remember cripplingly hot summer days, ice-box Limca, decrepit Hindustan Motors Ambassadors, two rupee chocolates, almirahs redolent of mothballs, hot puris and halvah, and the exertions of undernourished rickshawwallahs. I remember the Nilgiris at Ooty, Jakoo Temple in Shimla, the sheer chaos of the check-in counters at Santa Cruz, and the amazing old bookstores of Connaught Circus. I remember the Indian Airlines Caravelles, five-Rupees-to-a-dollar, asking the operator to book a call to America, and the hard benches of Haryana Roadways buses.

Young FSOs serving in modern India cannot even comprehend what India was like back then, nor how utterly estranged our governments used to be. Was it just a dream, or was it really so? There used to be three flights per week between Delhi and Bangalore, all via Hyderabad. Truly it was so. The Imperial on Janpath used to be a tattered, fading affair. Sitting in her restaurants today, the old days seem like an improbable memory.

My dream even from a young age was to see my Motherland and my father’s land become the very best of friends, and for our people to come appreciate and value one another as trusted partners. Having seen the poverty of my grandmother’s adopted post-Partition home town, I prayed to see a day when India could achieve some measure of prosperity the likes of which we took for granted in Virginia. And I imagined a moment when America and India would not feel so many worlds apart, but would feel like two halves of the same whole.

The first time I flew non-stop between India and America on a Continental Airlines Boeing 777, I was moved by the miraculous banality of something so unattainably impossible just a few years before. Gone forever the Heathrows, Frankfurts, and Schiphols; our nations and peoples no longer needed European via media. With the advent of the internet, what further need of Standard Trunk Dial rate cards? And when I worked on the visits to India of Presidents Bush and Obama, I marvelled at the utter transformation of our governments’ relations.

That I have lived to see all of this with my own eyes is blessing enough. That I have contributed to America’s diplomacy in forging a strong partnership with India is an even greater privilege. That India and America now exist — each in their respective hemisphere — as mutually friendly titans and arsenals of democracy and pluralism, however strivingly imperfect — is the realisation of a long held dream. The work is not complete; much remains to be achieved, but we are well on our way. Americans and Indians, 1.6 billion of us, are combining our energy and values to help ensure a brighter future for the planet.

The light of India’s civilisation has illuminated the world for millennia. From the divine discourse given by Lord Krishna at Kurukshetra to the wisdom dispensed so lovingly by Swami Satchidananda in the rolling green piedmont of my hometown in central Virginia, India’s cultural reach is vast beyond measure, and has touched so many far beyond her shores.

On the 70th anniversary of the Independence of modern India, I offer to all Indians my respectful and most affectionate greetings as an American diplomat, son of an American mother and Indian-American father. May our two countries grow ever closer, may we work together to alleviate suffering, improve lives for all on this planet, strengthen the common good, defend our democratic values, and strive together for a better tomorrow.

Recent Comments