By Girija Madhavan

The flowering trees in Mysuru’s parks and gardens begin to bloom early in the year. The city planners of long ago, planted them so that each month, starting in early spring, would have some flowers to brighten the landscape. There was even a pattern of colour; first the deep pink of the Tabebuia followed by its brilliant yellow twin, the Jacaranda’s purplish-blue, delicate mauve-pink of the cassias and, in May, the flaming scarlet of the “May Flower” or Gulmohar.

When the first lockdown for Covid-19 was announced on March 25 this year, a few Gulmohars in Yadavagiri were already putting out buds and blooms in anticipation of being covered later by masses of scarlet flowers speckled with white. They are not indigenous to India. Naturalist M. Krishnan quoted the saying “the Gulmohar is a strumpet from Madagascar”! They are now being replaced as avenue trees as the large ones with their shallow root systems, crashed down quite often, as dramatic in death as in their flamboyant appearance. But in 1950, the road was lined on both sides with them, a spectacular burst of colour.

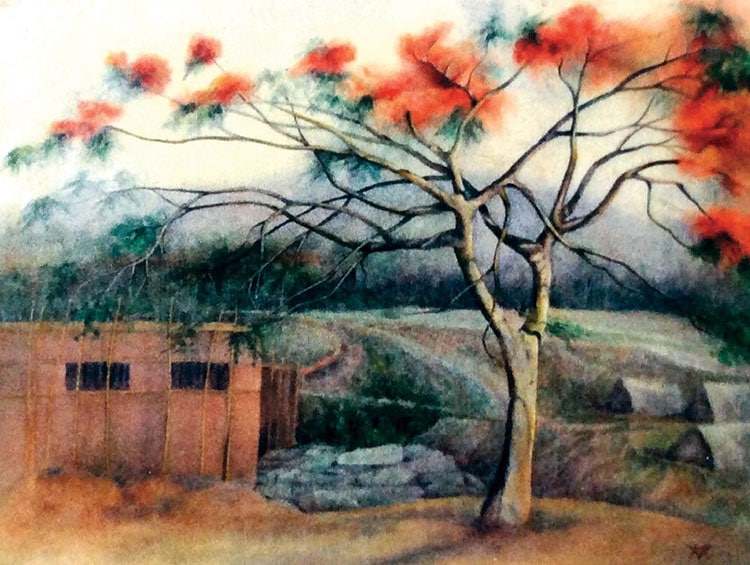

Yadavagiri then was considered to be an extension of the residential area of V.V. Mohalla, the postal address had to mention “Yadavagiri Extension”. A hilly land, the ground sloped steeply away from the main road, to the valley below behind the Akashavani Station. This area is still known to locals as “Handi Halla” [pit of the pigs] and the “Dhobi Ghat”. A footpath, with stone slabs straddling a deep ditch, led to a higher level ground on the opposite side. Roads have now been laid and houses constructed in that area. Seven decades or more ago, huts were sprawled across here, low walls of red earth with triangular roofs of thatched coconut fronds, bleached grey by the sun. These were the homes of itinerant workers called “Woddas” and the clutch of hutments was known “Woddara Jhopadigalu” [huts]. The Gulmohar avenue in bloom and the huts beyond are a memory etched in my mind.

The Woddas are not to be seen nowadays nor are they remembered except by the very old residents of the area. They were poor and toiled at difficult jobs, digging foundations, carrying loads of bricks or moving stone blocks. Without bulldozers, earth-movers and forklifts, building work was much more arduous. Their hard lives were said to be the cause of their low life expectancy.

The Woddas had their own language, based on Telugu, to form a unique dialect. Without electricity, sometimes oil lamps glimmered in the settlement. At times I could sometimes hear drumming from the distance. An insistent four beat rhythm would throb till late at night. What were their arcane rituals, myths or art if any? A friend of mine, gave me a rare insight into Wodda life. She had heard the story from family friends who had built a house with Wodda labourers excavating the foundation.

During the digging, red-mud spheres like upended pots, were found clustered together. The leader of the Woddas, a grizzled elder, identified them as termite nests. He circled them cautiously, tapping the tops of the structures. He suddenly stopped, resting his hand on one, saying the Queen ant was in it. He was proved right when the nest was broken and the large, ugly insect was found, unmistakably the Queen. His eye then alighted on a weedy youth in the group of workers whom he singled out.

He ordered the boy to eat the queen ant as it held all sorts of health giving properties. The poor boy’s protests were to no avail and the others laughed as he hopped around struggling to chew and swallow the insect. What other knowledge of fauna, flora or herbs have we lost, she wondered, now that the way of life of these simple folk has disappeared.

Opposite the Mysuru Railway Station and the Railway Office is Jeevanarayana Katte, a sunken square bounded by high banks. Now the Mysore Medical College Auditorium stands in the tidy grounds and flower sellers sell strings of jasmine, yellow marigolds and purple asters on the embankment. Some outdoor events of the Dasara Exhibition were held here.

“Gunboat Jack” the daring motorcyclist, did laps on a circular sloping course, loudspeakers blared film music. There were merry-go-rounds and shops. A twelve year old, I was tempted by sugared almonds in a sweetshop there. Before the shop-man could put his hand into the bottle, Mukta, my mother, asked if the sweets were “untouched by hand”. The shop-man’s angry reply was “All touched by hand. Are you not an Indian, don’t you eat with your hand?” Mother’s reply was “I am an Indian, but I eat with MY hand not yours.”

During the rest of the year Jeevanarayana Katte lay empty but for grazing cattle or stray dogs. On the embankment, however, were shacks selling toddy. The Woddas would go there; men and some women too, would sit on the ground with clay or black-stone pots in front of them, drinking the liquor. Children, too small to be left alone, would accompany the parents. The little ones were sometimes pot bellied, their hair tinted with a pale colour, symptoms of malnutrition. Playing rhythms on their drums, perhaps dancing, or drinking to escape their sorrows were the small pleasures of Wodda lives. Nobody spoke for them then and now they may have lost the old ways of life, hopefully for the better.

The Woddas were doing the hard slog work, not only because they were poor, but because they were at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, and no one cared for them in order to uplift from the cesspit they were put into by the Mysuru community, who should have been ashamed. If any community deserved special support, it was not Gowdas or Lingayats, but these Woddas. Stupid Nehru government instead of classifying a whole swathe of communities as backward, should have focused on those who were called untouchables and communities like the Wodda community. at the lowest layer of caste hierarchy. There were some who were excellent cobblers too.

The new : ” Woddas” are the immigrants who suffered because of Modi;s idiotic Covid-19 lockdown without making arrangements for these economically backward group of people to live somewhere.

In the independent India today, every community wants to be classified as Backward!