By Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik – Author, Speaker, Illustrator, Mythologist

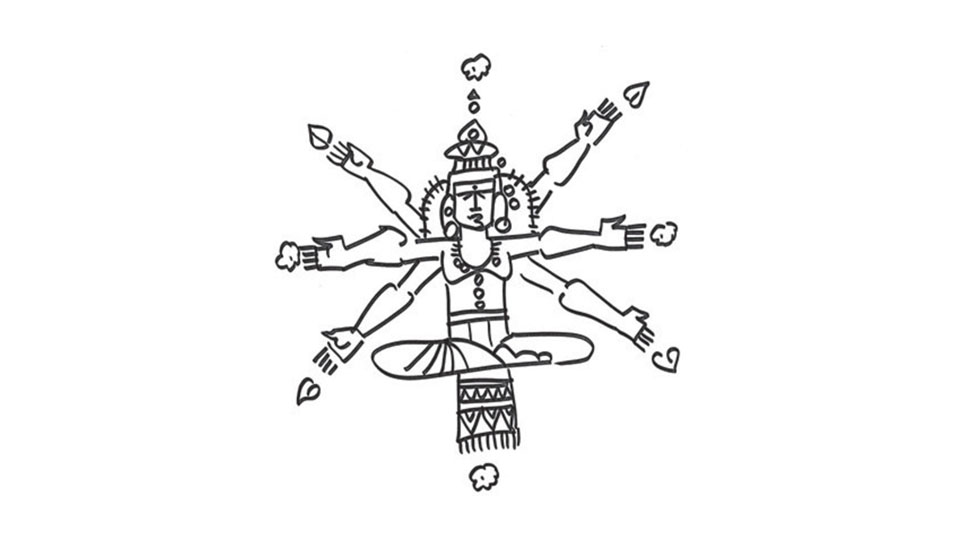

If you walk around a traditionally-built Hindu temple, it is likely that you will see images of the guardians of the directions (diggapala): Kubera in the north, Yama in the south, Indra in the east and Varuna in the west, with Vayu, Chandra (or Ishana), Agni and Surya (or Nirriti) in the ordinal directions. There are two other guardians of directions: Brahma above and Sesha below, who are often ignored in art, but listed in text. These minor Gods of Hinduism play a key role in Vastu shastra, or the Hindu lore on space and settlements as they keep out negative energies and bring in positive energies from each of these directions.

The concept of 10 diggapalas reached its final form about a thousand years ago when grand Hindu temples of stone started being built across India. But the thought can be traced to the Gangetic plains where Vedic yagna was being performed 3,000 years ago.

In Vedas, we don’t have 10 diggapala, only five lokapalas: the four cardinal directions and the zenith. The deities of the four cardinal directions vary in different hymns and are very different from those seen in temples 2,000 years later. They include Agni for the east, Indra or Yama for the south, Varuna for the west, Soma for the north, and Brihaspati for the zenith. Yama in the south and Varuna in the west have remained relatively consistent over the centuries.

Some scholars have argued that the idea may have come from the cities of the Indus Valley where we find symbols suggesting awareness of, and value placed on, cardinal and the ordinal directions. This makes direction-Gods an extra-Vedic and pre-Vedic idea that eventually became part of the Vedas. This is speculation, of course.

The Vedic five guardians first became four lokapalas in Mahabharata, as do Satavahana inscriptions from Nanaghat and Gupta inscriptions from Allahabad. Even the Buddhists refer to four deities (chatummaharajika) who guard Buddha while he is meditating. Only Kubera, king of yakshas (hoarders), guardian of the north, is common in Buddhist and Hindu lists. The other three Buddhist guardians are Dhritarashtra, king of Gandharvas (celestial musicians), who guards the east; Virudhaka, king of Kumbhandas (pot-bellied gnomes), who guards the south; and Virupaksha, king of Nagas (serpents), who guards the west. This idea spread to China via Buddhism and merged with Chinese lore where the four directions are identified with four mythical creatures located in as constellations in the sky: dragon on the east, white tiger in the west, turtle in the north and red birth in the south.

It is only with the rise of Puranic Hinduism that there is reference to eight, then 10, diggapalas in texts such as Manusmriti (1,800 years ago) and Yogayatra (1,400 years ago). These deities start appearing on temple walls a thousand years ago. This idea also spread to Southeast Asia and we find eight directions being represented as divinities in the royal symbol of Majapahit kings of Java, Indonesia, in the 13th century.

The rise of Gods who control space in every direction happened a long period, over 2,000 years, from pre-Vedic to Puranic times. It reveals the human desire to control various cosmic forces that pull us in different directions and shape our fortune.

Recent Comments