By Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik – Author, Speaker, Illustrator, Mythologist

One of Vishnu’s forms is Mohini, the enchantress. As Krishna, Vishnu becomes Madan-mohan, he who enchants even Cupid. This winsome lover plays the flute and invites Radha to dance with him on the banks of Yamuna in the bower known as Vrindavana. Their romance is rediscovered. But it is a celebration outside the village, at night, in secret, reminding us all that love, howsoever true, is often at odds with the demands of society.

Last year around February 14, there were a group of people who attacked shops selling Valentine’s Day trinkets denouncing them for pressuring Indian youths with Western ideas like ‘going on dates’ and encouraging pre-marital romance (hence sex).

We Indians — and I guess many citizens of planet Earth — are generally squeamish with the idea of romantic love, especially one that does not manifest itself between a man and a woman bound by marriage.

If love has to be accepted in Indian society, it must be between an older man and a younger woman, both unmarried, and it must culminate in marriage. For other forms of love there are myths and epics, even novels and films, but no place in society.

But the problem with ‘love’ is that it refuses to respect the law of the land. A man can fall in love with a married woman. A woman can fall in love with a married man. A married man can fall in love with a married woman who is not his wife. And vice versa. A man can fall in love with a man. A woman with a woman. People can fall in love despite disparities in their social and economic status.

Little wonder then that in Greece, the Love-God was visualised as a childlike mischief-maker called Eros. The Romans called him Cupid. An avid archer, he carried two kinds of arrows — one tipped with gold, the other with lead. Gold-tipped arrows made people fall in love; leaden ones made them hate.

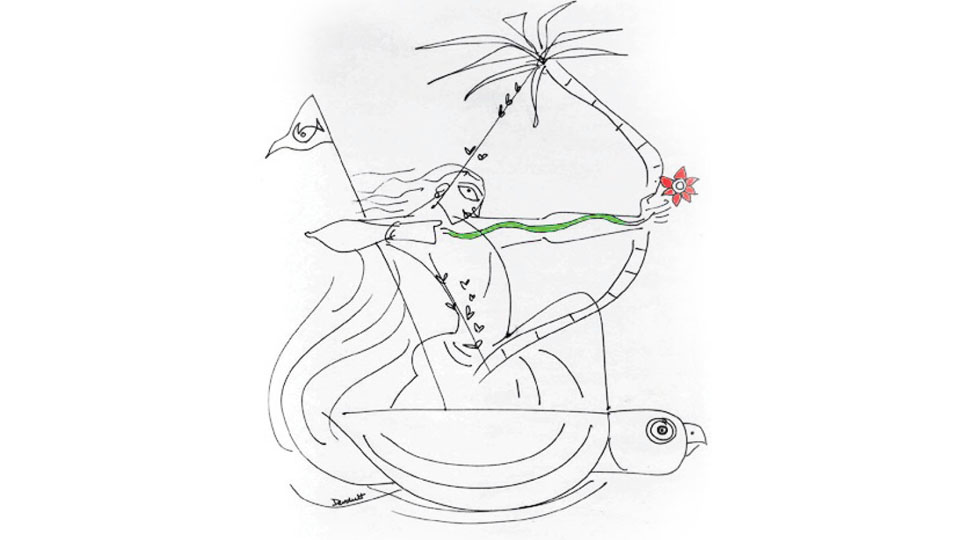

In India, the Love-God was also an archer. His name was Manmatha, he who churns the mind. Popularly known as Kama-dev, he entered every one’s life riding a parrot, holding aloft his fish-banner, raising his sugarcane bow and drawing his bowstring of bees to shoot flowers-arrows that stirred the senses, excited the heart and filled the mind with yearnings that often refused to align themselves with the rules of good conduct.

In the Rig Veda it is said that the world came into existence because desire for creation arose in the heart of the creator. In the Atharva Veda therefore, Kama-dev is described as the one who existed even before the Gods.

According to Brihadaryanka Upanishad, desire of the primal father for his first creation, the daughter, led to the creation of all creatures big and small. While the ‘result’ was good, the incestuous nature of the ‘cause’ made sages and seers wary of Kama-dev’s capabilities. In the Puranas, therefore, Kama-dev is reduced to dust by the supreme-ascetic Shiva.

The Gods had enlisted the help of the Love-God to make Shiva abandon his acetic ways, embrace a woman and father a child who would be a great warrior, a killer of demons. They had never anticipated such a violent response. In the violent response of Shiva lies the eternal conflict of all religions — that between the monastic ideal that offers spiritual bliss and the pleasure principle that offers material joys: Sex — the most tangible expression of union — was essential to rotate the cycle of life, yet yearning — the emotional component of union — was an obstacle to spiritual bliss.

If the plays of Kalidasa, Shudraka and Harsha are to be believed, there was a time in India when images of Kama-dev were worshipped in gardens during spring in festivals such as Vasant-utsava and Madan-utsava. At that time, there was no conscious effort to distinguish fertility from sensuality. Women were encouraged to bedeck themselves and walk on the streets, exciting the Gods, enticing them to share their heavenly delights with mortals.

But with the rise of monastic ideas, this erotic and romantic mindset had to be curbed. Spring festivals were stripped of their erotic charm. Kama-dev became Ananga, the bodiless one. It was hoped that by denying his form, the ideas associated with him would not corrupt the youth.

Suddenly, nearly 2,000 years after the heritage of sensual delights gave way to monastic ideals, we find that Kama-dev striking back through Valentine’s Day: a day when the deluge of advertisements and television programmes force us to think of romantic potentials and possibilities.

Only the vocabulary is Western

There is no denying that Valentine’s Day has its roots in the West. There is no denying that Greeting Card and gift manufactures of the world have made it popular in recent times to exploit the commercial opportunity it offers. Granted that ‘going on dates’ seems to be a very MTV-planted thought in the Indian psyche. Granted that ‘arranged’ marriages are still very much the norm in India. But the idea of celebrating love and fertility when winter is giving way to spring is hardly alien to Indian culture.

The timing of Valentine’s Day matches the timing of the ancient spring — and love-festivals such as Vasant-utsav and Madan-utsav. And it is no coincidence that festivals such as Lohri, Makara-Sankranti, Shiva-ratri and Holi are celebrated around this time.

Both Lohri and Holi are associated with bonfires, reminding us of the burning Kama-dev. Lohri is associated with harvest and fertility. It is the Pongal of the North. A time to worship the sun who enters the House of Capricorn (Makara). Capricorn a creature which is part fish and part goat in the Western tradition and part fish and part elephant in the Indian tradition is the emblem of Kama-dev. Holi is a festival charged with sexual energy as ribald jokes are cracked and men and women throw colour on each other. A fortnight before Holi, one celebrates Shiva-ratri, the night of Shiva, when the ascetic renounced his ascetic ways and agreed to marry the Goddess so that the cycle of life continues to rotate.

Today Kama-dev is no longer worshipped. But he exists. His symbols have been taken up by other Gods such as the sun and moon whose rays are supposed to heat the body with passion. In the Bhakti period, Kama-dev was visualised as the son of Vishnu and Lakshmi. Like Kama-dev, Vishnu is associated with parrots, bees, capricorn, butterflies, flowers, sugarcane, fragrance, beauty and an alluring mischievous smile.

One of Vishnu’s forms is Mohini, the enchantress. As Krishna, Vishnu becomes Madan-mohan, he who enchants even Cupid. This winsome lover plays the flute and invites Radha to dance with him on the banks of the Yamuna in the bower known as Vrindavana. Their romance is rediscovered. But it is a celebration outside the village, at night, in secret, reminding us all that love, howsoever true, is often at odds with the demands of society.

e-mail: [email protected]

Recent Comments