By R. Chandra Prakash

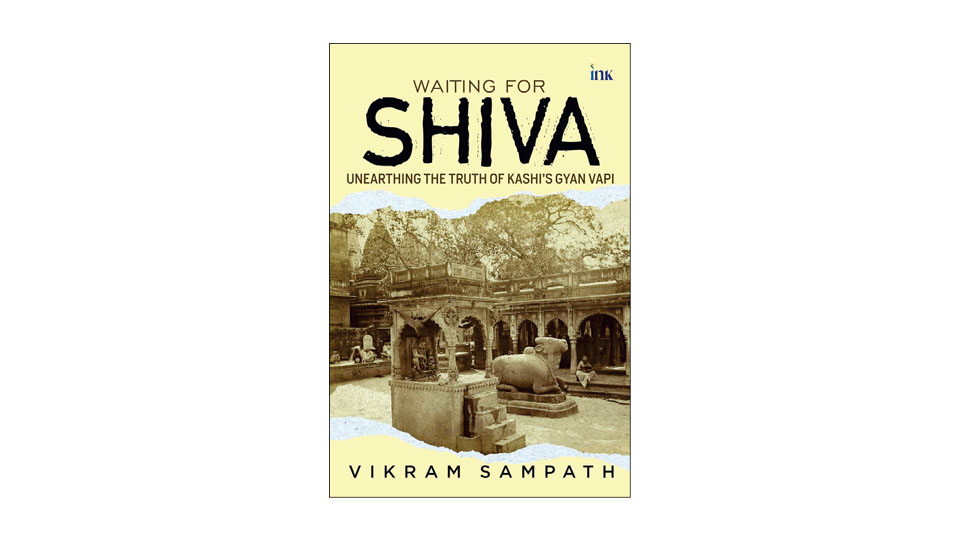

- Title: Waiting for Shiva: Unearthing The Truth of Kashi’s Gyan Vapi

- Author: Vikram Sampath

- Year: 2024

- Pages: 368

- Price: Rs. 699

- Publisher: BluOne Ink Pvt. Ltd., India

Sanatana Dharma, true to its meaning ‘perenniality’, has survived several millennia of political and religious attacks. Today it is being practised by nearly eighty percent of the population of the country. Islamic occupations of 1300-plus years, and more than two hundred years of Christian colonialism did severely affect the Sanatana Dharma. The partition of the country in 1947 on religious lines gave the impression that thereafter Sanatana Dharma will have scope to heal its wounds and grow as a resilient dharma.

But it is during the post-independence period that Sanatana Dharma suffered challenges to its very existence. Bharat’s rich religious heritage and cultural ethos were mortgaged to fake and fictitious ‘secularism.’

The Constitutional amendment to overturn the very sane Supreme Court judgement in the Shah Bano marital case in 1985, the passing of The Place of Worship Act in 1991, and many other similar steps taken by the Congress party giving the Muslims, who remained here after creation of Pakistan and their progeny, special prominence as a religious minority and using them as a vote bank added new tensions to inter-religious relations in the country.

Ram Mandir – A Political Turning point

The consequences of the re-emergence of Muslim political activities in the independent India became quite visible during the Babri Masjid / Ram Mandir dispute. Long drawn political and legal battles became the turning point. This was evident from the Jan Sangh’s / Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) campaign on Ram Mandir as a counter to Muslim appeasements by the Congress and a few other parties. As a consequence, Sanatana Dharma suffered a setback till the year 2014.

Victory of BJP in 2014 with its own majority in the Lok Sabha, and its return in 2019 with bigger majority than 2014, was largely the outcome of this religious divide. The Supreme Court judgement of Nov. 2019 in favour of the Ram Mandir, the successful construction and consecration of grand Ram Mandir in January 2024, seems to have ensured the BJP to have a hat-trick return in the ongoing Lok Sabha elections.

With the inauguration of Ram Temple at Ayodhya, not only a long felt need of Hindus has been fulfilled and religious aspirations realised but also the hurt feelings of millions of Hindu believers have also been assuaged. This is factually proved by crores of people who have taken a darshan of Ram Lalla within a very short time, with daily number of visitors being somewhere above two lakhs!

However, this fulfilment has triggered the desire to retrieve at least two more holy temple places — Gyan Vapi in Kashi and Lord Sri Krishna in Mathura.

Gyan Vapi Temple/Mosque

Vikram Sampath’s book Waiting for Shiva: Unearthing the Truth of Kashi’s Gyan Vapi is a very timely work in the above context. Despite the visual proof, a part of magnificent old temple attached to the mosque and the very name of Gyan Vapi symbolising Hindu Sanskrit roots, there has been stiff opposition from Muslims and their organisations contending that the Gyan Vapi mosque is not built by partly breaking down the ancient Shiva temple. This has further increased the Hindu-Muslim divide.

The History and Sanctity of Kashi

The author has established in great details that the city of Kashi, Varanasi, with its multiple names, has a long religious sanctity not only to Hindus, but also to the Buddhists and Jains. And its Gyan Vapi Shiva Temple of the past was its central religious magnet for Hindus all over the country from time immemorial. The belief of Hindus that dying in Kashi or at least to be cremated there, is the only way of getting Moksha is the corner stone of their belief. In that it is both a Historical City and the City of Light, City of Enlightenment.

Even while the Gyan Vapi Shiva temple is the epicentre of Kashi, the author in great details proves that the city has had multitude of Lingas all over the city. The author provides clarifications for mythological meanings and relevance of these Lingas in Hinduism.

The Conflict

Vikram Sampath elaborately narrates the historicity of the conflict between Hindus and Muslims in the context of Gyan Vapi. (The name means Well of Knowledge). The Chapter The Spark in the Tinderbox contains the origin and progress of the conflict ever since Britishers took control of India. There have been records of multiple Hindu-Muslim riots leading to legal tangles in British Courts. Several reports by committees of British Officers provide testimony to hard feelings on both the religious groups.

The ownership of the lands on which the Gyan Vapi mosque and the partly demolished Shiva temple are located were also the subject of long drawn legal battles. So also the earning of rents from parts of these lands. These legal battles continued after the Independence of the country.

The politicisation of these conflict was the automatic outcome of post 1990 scenario. In the post The Place of Worship Act of 1991 and the demolition of the Babri mosque, Mulayam Singh government added fuel to fire by banning puja at Gyan Vapi ruins, even though it was being carried on for a very long time.

Shringar Gauri And the ASI Survey

Since 2020 the Sringar Gauri case filed by five women and the never tiring advocate Hari Shankar Jain have added a new dimension to the Gyan Vapi temple/mosque case. The details provided in this book are a record of concurrent history of this issue. The dramatic turns and twists of legal battles from the local courts to the High Court and the Supreme Court and the entry of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) are detailed by the author.

The Wait Continues

One cannot discount the fact that the sight of mosques visible dominantly over the partly demolished ancient Hindu temples, both in Kashi and Mathura, even after 75 years of independence is not only painful reminders of the historical wrongs done to Hindus by the invaders, but also very demeaning in the changed social equations.

When the ‘other’ happens to be Hindus, the majority of the country, which has borne the brunt of religious partition and post independence discriminations, this inability to reclaim its religious heritage is surprising.

Sanatana Dharma today stands at a crossroad. Should it, in an independent country, continue to suffer the ignominy in this manner at the altar of fake secularism? Or should it recover and reconstruct, at least a few important temples, as a testimony to its historical religious eminence? Well, time alone will provide the right answer.

Recent Comments