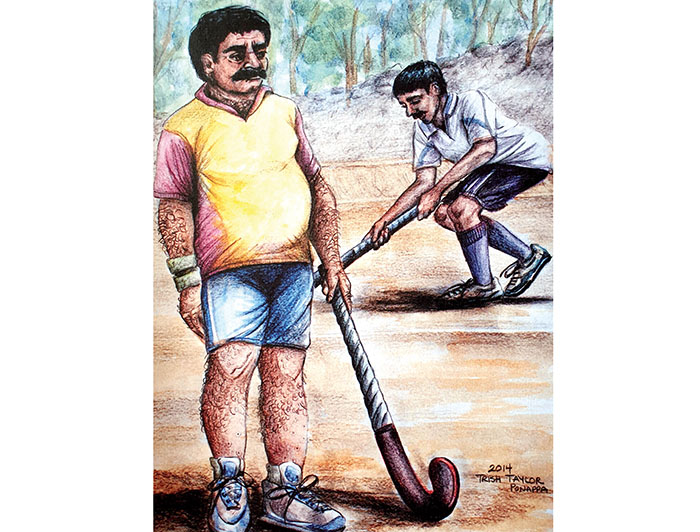

By Dr. Tilak Ponappa

Despite the hype and glamour that surrounds other sports, especially cricket, hockey holds a special place in the hearts of the people of Kodagu. The Family Hockey Tournament remains a popular event and there are several talented youngsters who emerge in these matches. Many such players from rural areas learn their craft on natural surfaces. Since all major tournaments are now conducted on synthetic surfaces and youngsters from the more affluent countries begin their hockey journeys by playing on such grounds, it confers a great advantage to players from these countries.

Fascinated by the interest and passion for hockey in Kodagu and not missing any Family Tournaments in his home district, Dr. Kuppanda Tilak Ponappa draws examples from other sports and presents the argument in this article that hockey players should be able to adapt to different surfaces including natural ones. Perhaps, such a move will ‘level the playing field’ and enable our once great subcontinental teams to compete with the very best in the world. — Ed

The early days

To people of the Indian subcontinent, hockey refers to ‘Field hockey,’ and is distinct from ‘Ice hockey’ that super-fast, ultra-violent sport played in the frigid northern latitudes.

Field hockey was introduced to India by the British during the colonial era. Indians soon took to the game and were quickly dominating the English teams, and indeed, everyone else. Indian players were famous for their skilful dribbling, clever passing, body swerves and general artistry.

India remained the pre-eminent team in the world for many decades. In the Summer Olympics, India was dominant between 1928 and 1956, winning gold in Amsterdam, Los Angeles, Berlin, London, Helsinki and Melbourne. Another Indian gold medal in Tokyo (1964) was sandwiched between the two Pakistani triumphs of 1960 and 1968.

Cracks in the pre-eminence of subcontinental hockey became evident in the 1970s. During this period, the victory in the World Cup final over Pakistan in 1975 proved to be a high point for India. By the time the Moscow Olympics rolled around in 1980, India was no longer a dominant force. That year, although India did win its eighth (and last) Olympic gold medal in hockey, it perhaps lacks the lustre of the previous seven golds, as many of the best teams of that era boycotted the tournament for political reasons.

The partition of India and the creation of Pakistan saw the two neighbours play each other in many an epic battle, featuring their exciting style of hockey. Pakistan produced numerous excellent teams that won three Olympic golds, three silvers and two bronze medals from 1956 through 1992; in addition, our neighbours have won the prestigious World Cup four times having last triumphed in 1994. Sadly, neither of these teams rules the sport any longer.

In the past, there was something about a hockey victory by India, especially during the colonial era and soon after Independence, that gave the sporting public a great sense of pride. But things change, and many factors have resulted in a host of European teams as well as Australia, New Zealand and Argentina being major powers in the sport.

Why do teams from the Indian subcontinent no longer dominate hockey?

All sports evolve over time. Technologically advanced countries probably analysed the all-conquering Asian hockey teams and developed means to counter them. Gradually, the Europeans and Australians began to catch up to the subcontinental teams and eventually surpass them.

Furthermore, numerous changes were implemented in the rules of hockey. Some of these were ostensibly to speed up the game and make it more visually appealing to television audiences; although the end result may have been detrimental to the Indians and Pakistanis. A major change was the switch from natural to synthetic surfaces that were inaccessible to many players in these countries.

I suggest that, at least in India and other developing countries, there would be much to be gained by returning to the natural surfaces where the game was first played and rose to popularity. In order to emphasise this issue, perhaps we can look at the way some other sports are conducted.

A case in point would be ‘lawn’ tennis where the surfaces vary depending on the tournament. Two of the major championships, the Australian Open and the US Open, are now played on synthetic courts. Wimbledon, on the other hand, is played on grass; whereas the French Open is conducted on clay.

Many giants of the sport have had limited success in adapting to courts that were relatively unfamiliar to them. For instance, the American stars, Jimmy Connors and Pete Sampras were unable to conquer the red clay of Roland-Garros at singles, although they had great success at the other major tournaments. A Wimbledon title eluded Ivan Lendl, though he won multiple major tournaments on surfaces other than grass.

All sports change over time. Modern-day tennis players use racquets with large sweet spots and are able to generate incredible pace and topspin. However, the introduction of these enormous racquets means that we seldom see the kind of finesse and ‘touch’ exhibited by the brilliant John McEnroe, our own Ramesh Krishnan or his father Ramanathan Krishnan.

While considering cricket, especially the exacting Test match version, there is little question that the playing surface has a great effect on performance. In fact, much of Test cricket’s charm results from the pitch’s characteristics. The nature of the soil, the amount of grass on the surface and the methods used in the preparation of the pitch, all contribute to the ebb and flow of the game and its ‘glorious uncertainties’.

Consequently, the ability to adapt to the initial state of the surface, as well as its changing nature over a five day Test match is vital to a cricketer’s success.

There is an abundance of sporting talent in the little district of Coorg (Kodagu) in Karnataka.

The hardy people of these hills have excelled in various athletic endeavours, but the sport that seems to be closest to their hearts is hockey.

The annual ‘Hockey Festival’ in Kodagu is a significant event in the local calendar. Hundreds of Kodava families participate in the tournament wherein the skills of many talented rural players are on display. Although the fields may be grass or gravel, the matches are often riveting, indicating that a synthetic surface is not imperative for the sport to be exciting.

Despite the all-pervasive presence of cricket in the media, and the general impression that interest in hockey is on the wane, it is encouraging to note that there remains isolated pockets in India, including Kodagu, Punjab and Odisha, where hockey still holds a special place in the hearts of sports enthusiasts.

Conclusion

India was once a great hockey playing nation. However, for various reasons, it has been many decades since teams from the Indian subcontinent have dominated the sport. Since the inaugural World Cup in 1971, India’s best result in the competition was achieved way back in 1975, when they were crowned champions. Unfortunately, replicating this early success in the prestigious tournament has proved to be elusive.

The bronze medal in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics was a significant achievement considering the country’s previous Olympic medal at hockey was earned in the boycott-marred, truncated Moscow Olympic competition of 1980. Although the silver medal in the recently conducted Commonwealth Games of 2022 is a creditable achievement for our men’s team, losing 0-7 to the mighty Australians illustrates the gulf that needs to be bridged before we can get back to the very top of the sport. As the country develops on all fronts, one looks forward to more progress in the sport and hopes that appropriate steps are taken for the team to reach the summit again. Perhaps making a pitch for putting the ‘field’ back in hockey will be one such measure.

How can we attract more youngsters to hockey?

1. Allow the use of different playing surfaces

A talented young hockey player in rural India may not have access to artificial turf. The skills needed to succeed on a natural surface are different from those required for synthetic surfaces. By the time the player is proficient enough to be selected for a training facility with access to artificial surfaces, new skills will have to be learned and old ones unlearned, putting the youngster at a disadvantage.

The use of artificial turf, often coloured blue, was thought to facilitate television viewing. Today, however, multiple, high-quality cameras would likely capture the nuances of the sport regardless of the playing surface. Perhaps it is time to play major international hockey tournaments on either natural or synthetic surfaces, depending on convenience.

The teams that can adapt to different types of surfaces will be more successful as in the case of a tennis player who is able to win all four major tournaments and earn the coveted Grand Slam, or a cricket team that wins at home and abroad.

2. Reduce the chance for injury and the need for protective equipment

While playing hockey on uneven surfaces and indeed on any surface, perhaps we can take a step back for reasons of player safety and ensure that the ball remains on the pitch, or not more than a few inches above the ground, except when ‘scooped’. Strong enforcement of the old rule of ‘sticks,’ whereby a hockey stick may not be raised above shoulder level when taking a shot, would also reduce the likelihood of injury.

3. Encourage the scoring of more field goals

Modifying rules to enable the scoring of more field goals and reducing the emphasis on ‘corners’ may well make the game more exciting. To this end, perhaps doing away with frightening drag flicks that could seriously maim defenders would be useful. Again, such measures will also reduce the necessity for expensive protective gear that may not be easily available or affordable to poorer countries. Although not related to this argument, reinstating the unique ‘bully’ to start the game would restore some old-world charm.

4. Look after the interests of hockey players in the developing world

As in most walks of life, money matters. Compared to many developing countries and indeed several other nations that are considered “advanced,” India has become relatively wealthy after shrugging off the colonial yoke. Thanks to shrewd marketing and administrative strategies, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has harnessed the passion of our enormous population for cricket.

Consequently, the BCCI is flush with funds and does not have to kowtow to the cricket boards of other countries. If our hockey administrators were as influential as the BCCI, changes proposed by the world body that may prove to be detrimental to the sport in our country could be opposed.

Also, popularising hockey with the country’s youths would be an important step forward. Promising young players need to feel a passion for the sport, pride in the country’s past success and perhaps view hockey as being just as glamorous as cricket.

5. Identify talent early

A scientific approach to identifying and grooming promising players is essential. In the highly competitive world of American football, players are constantly evaluated for parameters pertinent to that sport. Very often, but not always, elite athletes end up being exceptional football players. Conversely, some of the greatest professional players have not necessarily been the best athletes. Apart from being conversant with modern techniques, our hockey coaches must pick players who are not only sufficiently athletic but also have the temperament to succeed at the highest level. Excellence must be rewarded.

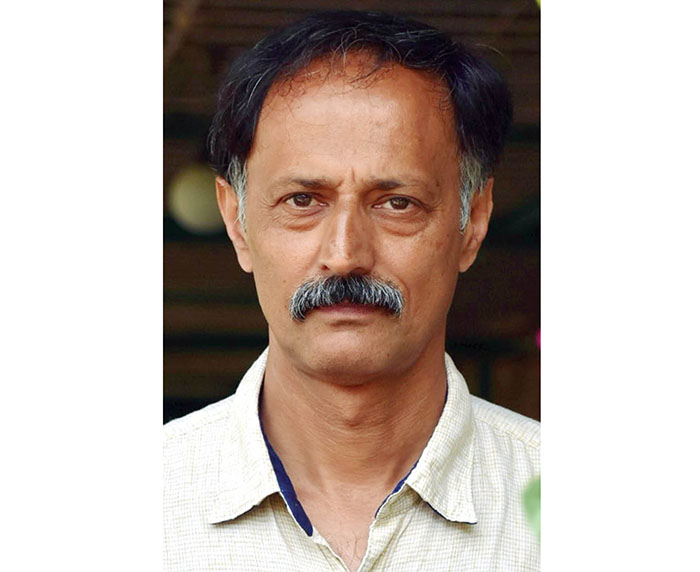

Dr. Tilak Ponappa is a planter based in Kodagu. Previously, he used to conduct scientific research in the area of plant biology. He is also the author of the novels, ‘Joy in Coorg’ and ‘The Cougar.’ The author is grateful to Dr. Ashok Menon for his valuable suggestions. Dr. Tilak Ponappa can be reached via email: [email protected]

Dr Tilak has rightly analyzed, ” What ails Indian hockey “, which is an oft repeated phrase by the main stream media, whenever India loses !

He has, in his article demonstrated how Indian hockey can be redeemed and played the way it was played in the yester years.

Hi brilliant analogy , drawn from the other sports, like tennis and cricket, is a definite eye opener for the czars of Indian hockey.

It’s never too late!