By Vighnesh Hampapura

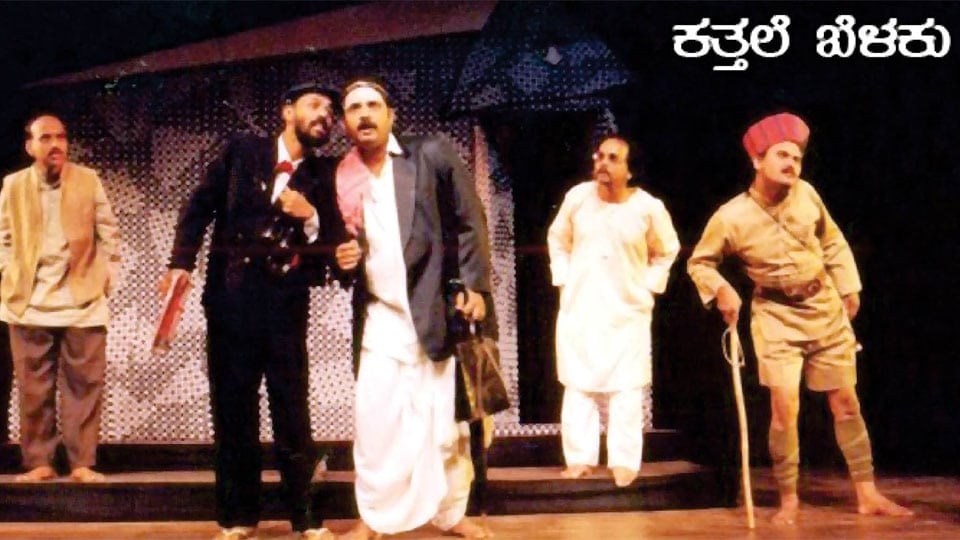

Many have dubbed ‘Kattale Belaku’ philosophical. There is a disillusioned playwright (Jagadish Manavarte), who has material grouses with theatre: he lives in his father’s house; all the plays brought him was fame. There are two drama (tic) fellows behind him, a director (Hulgappa Kattimani) and a producer (Prashanth Hiremath), persuading him to write them a play. As they enact different stories to him, for inspiration, with a list of conditions to please the audience, the play does touch fundamental questions — philosophical, one might say — of theatre, of literature in fact.

These questions are universal. Even today, they are thrown at writers and playwrights in lit-fests, to kill time: What should one write about? How do you draw the line between fact and fiction? Should fiction be realistic? Who does one write for? Do myths, history, and imagination have significance? Rather than answering the questions, ‘Kattale Belaku’ explores them.

Here enters satire. As the two glib-talkers perform different scenes with heightened drama that yesteryear theatre demanded, the absurdity of their theatrical choices hits us. Cliché characters, overbearing music, generic stories, puns and rhymes in spoken dialogue: amidst the realistic setting of a playwright’s house, these elements mock themselves.

Theatre, as it was, is satirised: the murder must take place on an Amavasya, the dagger must have pearls on them, the killer must turn and sway; at a point, a morose tape-recording is switched on to heighten the melodrama. A police-officer (Shaikh) even mouths: “all this happens only in literature.” Accordingly, ‘Kattale Belaku’ seems to peel the layers of the game of shadows-and-lights to reveal the dishonesty of theatre.

Ridiculing this snobbery, the incidents outside the playwright’s house mimic the ‘absurd’ stories presented inside by the director. A man (Pramila Bengre) is falsely accused of killing his wife and her lover. A rich lady (Saroja Hegde) wants to kill her husband for his wealth and live with her driver (Ramanatha). A poor couple (Vinayak Bhat and Nandini Hiremath) are chased away by their landlord. These real-melodramatic incidents retaliate the label of a ‘cliché’: A counter-satire to the previous satire, exemplified in the police officer’s question: “is this only a play, or is it all really happening?”

The techniques used to achieve this confusion in the play is commendable: the dramatis personae — the couple, the lovers, the accused — hide in the darkness of the playwright’s house, and scenes of the play are narrated in bright light. Clearly, a reflection of theatre: the real audience sit in the dark, the actors share some lights. Three vagabonds dress like theatrical clowns, asking of the queer incidents in the town: “would anyone pay money to watch this with a ticket?” — exactly what we all do. And then when the characters run away from the playwright’s house because he resolves to write no more, it is as if they were waiting to be written onto pages, now walking away without success. Add to that the fact that ‘Kattale Belaku’ is itself a play: were these people really real? We’re going in circles.

And we do only that. These explorations never come together; they remain disparate ideas, “roaming on stage” as the playwright puts it. Confusion could be the only answer to these questions, of course; but that is for classroom discussions, not an evening in theatre. The play does not work because Indian theatre has now long surpassed these questions and dilemmas.

Rangayana, and its brilliant actors, are themselves frontrunners of extraordinary ideas and experiments in theatre: which other institution can boast of a night-long ‘Malegalalli Madhumagalu,’ or a ‘Halegannada Sri Ramayana Darshanam’? There: history and myth. From a ‘Julius Caesar’ that contested the structure of the stage, to a ‘Shikari’ adapted from a novel, Rangayana has done it all. The ideas of these plays, and many others, have had richer material to offer, and have surrogately responded to the imperative questions of ‘Kattale Belaku.’

The greatest satire of the evening, then, was the fact that Rangayana performed ‘Kattale Belaku’ in 2019. This is not to tarnish the ingenuity of the play, an ingenuity that is passable three decades later. The audience has outgrown the ponderings of ‘Kattale Belaku.’ Rangayana seems to have taken a dialogue from the play too much to heart: “People will watch the play — why won’t they? Don’t we know what kind of play the people want?” Well, Rangayana is the only reason to watch the play: the tedious watch is saved by the effortless delivery of the artistes.

Writing about this play, Sriranga had himself suggested that his style and technique had to improve with each play, that theatre had to evolve with time. And theatre has evolved: in Karnataka, at the very Bhoomigeeta.

For Rangayana, when its creativity ripening every year, when its artistes have only a few years in service, to revive ‘Kattale Belaku’ is a disappointment.

But since revivals are important, there are more than a couple of alternatives the audience would love: Chirebandi Wade, Tughlaq, En Hucchurree Yak Hingadteerri? Please?

Recent Comments