By Girija Madhavan

In Mysuru, the Horticultural Department recently organised an “Ikebana” workshop. This traditional Japanese art was enthusiastically received.

Ikebana [meaning “Living Flowers”] began as votive offerings in Japanese Buddhist temples some six centuries ago. Later it was recognised as an art-form, which retained Zen symbolism. Abbot Senkei, also called Semmu, who lived by a Lake, started the style of Ikebana called Ikenobo [“Flower Arrangement of the Hermitage by the Lake”].

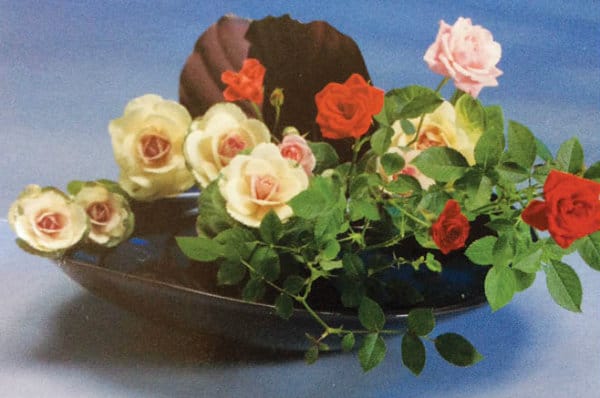

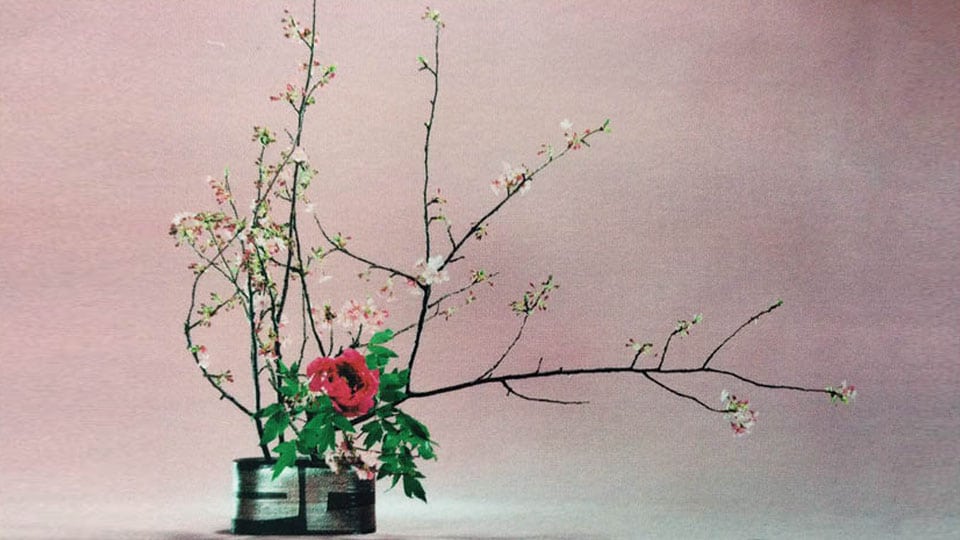

Arrangement by the Ichiyo School of Ikebana.

There are three main types of Ikebana:

- The Nageire School of natural-looking, free-standing arrangements which are a simplified version of the older, oversized and formal Rikka style used in temples.

- The Ohara-Ryu School created by “Flower Master” Unshin Ohara which features the “Moribana” arrangements of massed flowers.

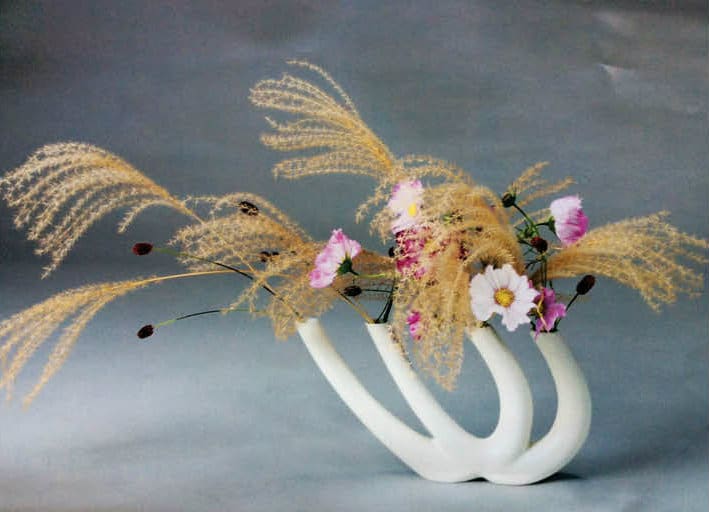

- The Sogetsu School of Grand Master Sofu Teshigahara set up in 1926. This style conforms to the classic rules of Ikebana but allows for creativity and thematic design. There are also free style arrangements using unconventional materials and abstract forms called Ze-nei-bana or Avant Garde.

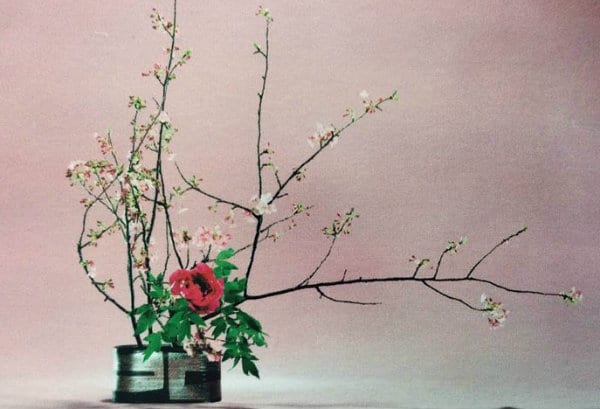

Arrangement by the Ko-ryu School.

The heart of the traditional Japanese home is the “Tokonoma,” a little alcove with a raised platform. The back wall usually displays a painted scroll of flowers, landscape or calligraphy. Under it stands an Ikebana arrangement in a prized container as a single composition. Ikebana is no longer confined to the Tokonoma or the Tea House, where it was part of the setting for the Tea Ceremony. It is used now as an art form in everyday settings.

Ikebana is meditative, aiming at inner calm and harmony through contemplation of line, form, space and knowledge of plant forms. Basically the compositions have three main lines. The tallest branch or sculptural line represents “Sky” or “Heaven”. The second, two-thirds the size of the first, stands for “Man”. The shortest, at the base, is “Earth.” An uneven number of flowers complete the composition. To ensure that flowers stay fresh, stems are cut on a horizontal slant under water; some are treated with vinegar or hot water, some are seared with a candle flame. Thorny plants are not used.

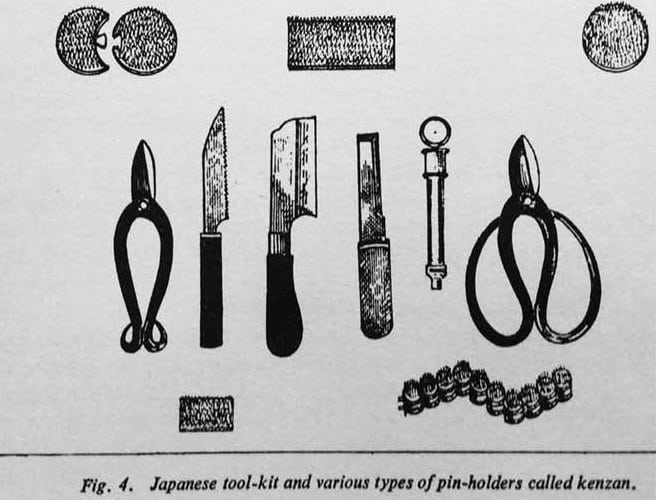

Tools used for Ikebana.

A pair of secateurs [or sharp scissors], a knife and, most important, pin holders called “Kenzan” made in many sizes, are the basic tools. The classic Kenzan has a half-moon cut away, wherein a smaller pin-holder fits. Appropriate vases are chosen; shallow ones for the Moribana or tall vases for the Nageire. Artists can innovate with original or imaginative containers found locally. The Nageire style reminds me of a stage-set in the Imperial Palace in Tokyo for a dance recital by Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra to inaugurate the Festival of India in 1988. In the corner was a large pottery urn with a tall Nageire arrangement of pine branches [representing eternal life], chrysanthemums [the insignia of the Emperors as well as a symbol of nobility] and plumes of grasses [adjustability or obedience to order]. No pin holder was used, crossed bamboo slats being inserted into the narrow neck of the vase to balance the precarious floral arrangement. Guru Kelucharan decided to use this as a prop for his portrayal of a shy deer sheltering in the woods. As he hid close behind it, his hands miming the movements of the animal, the Masters who had created the floral piece became palpably nervous. Great was their relief when the deer at last pranced into the open stage.

Sogetsu School

The Japanese observe the cycles of nature [which we call Ritu]. The “Flowers of the Four Seasons” are celebrated in paintings and designs on lacquer-ware and textiles. Specific blooms are associated with months. The cherry blossom or “Sakura” represents spring. Seasonal flowers get due recognition in floral compositions.

Ikenobo arrangement

Cities like Delhi, Mumbai or Chennai have flourishing Ikebana “Chapters”. Mysureans found a short Ikebana workshop giving them many creative ideas and they may well evolve a fusion of Indo-Japanese styles for decoration and art.

[Flower photographs: Courtesy of the annual calendar from the Embassy of Japan, New Delhi.]

Recent Comments