By T.J.S. George

Many things will be said, and more remembered in silent wonderment, about Girish Karnad, who appeared as one person but was in fact a congregation of identities — actor, playwright, director, essayist and, never forget, Urban Naxal. He was a shaper of his times. He made seminal contributions to the literary heritage of his country and, disturbed by the gathering clouds of sectarianism, turned an activist influential enough to invite death threats. He ignored them.

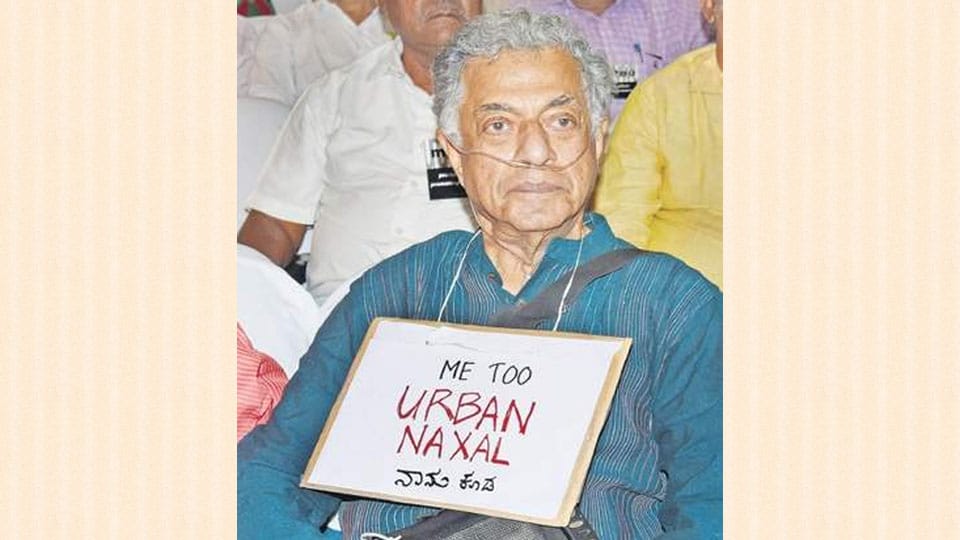

Girish Karnad was a personification of the courage that came from convictions. Wearing a placard round the neck with the legend, “Me too Urban Naxal,” was his way of standing up for rationalists who had fallen to assassins’ bullets — Dabholkar (2013), Pansare (2015), Kalburgi (2015). “Accusations against rationalists are a complete hogwash,” said Karnad. “It is scary because they believe they can do what they want… If speaking up means being a Naxal, then I am an Urban Naxal. I am proud to be part of the hit list.”

Like all men of destiny, Karnad gave to the world more than he took from it. (Indeed, he seemed to take nothing at all, no gun salute, no religious rituals, no public functions, on his departure.) He gave to theatre and cinema more than one man’s fair share. He went on to play his role as citizen as well, pushing forward causes that needed advocacy.

He was lucky to blossom in what was India’s best time, the 1950s – 1960s quarter century. By mid 1970s unfamiliar political trends would start crushing the spirit of India, reaching climactic points from the 2010s when intolerance, the very opposite of the Sanatana Dharma foundations of the idea of India, would take centre stage and turn India into a collection of mutually suspicious little Indias. Karnad became part of the creative tide that took India to marvellous heights in the early stages of that period. In the disruptive years, he walked bravely into realms where angels feared to tread.

The blossoming years were inspirational. His generation was rich with creative minds that raised questions without pretending to answer them. It was indeed a nest of singing birds – Badal Sarkar (born 1925) in Bengali, Mohan Rakesh (1925) in Hindi, Vijay Tendulkar (1928) in Marathi and in Kannada, B.V. Karanth (1929), U.R. Ananthamurthy (1932) and P. Lankesh (1935). Two signature qualities helped Karnad (born 1938) to rise to his own heights. The first was the versatility of his talent that made him shine in acting, writing, cinema, direction and television in addition to drama. Lankesh was the only contemporary who showed similar ambidexterity, adding also poetry, fiction and journalism to his repertoire. Yet, Karnad soared higher because of his other signature quality: The ability to make his plays go beyond Kannada and to build for himself an international profile through a series of leadership roles in Pune, Delhi, London and Chicago.

With Ananthamurthy, his collaborative association went deep. Ananthamurthy’s classic Samskara was turned into a film in 1970 with Karnad doing the screenplay and Patabhirama Reddy directing. It was a trend-setter marking the start of parallel cinema in Kannada and the navya (renaissance) movement. When Tughlaq was published in English, Ananthamurthy wrote the introduction in which he said, “There is no play in Kannada comparable to Tughlaq in depth and range.”

Was Tughlaq Karnad’s best play? It certainly was the most celebrated. For one thing, its appearance in Kannada in 1965 was followed by Hindi, Bengali, Marathi and English performances. Somewhere in some form it has been getting continuously staged. For another, the play reflected disillusionment over Nehruvian dreams, thus giving it a contemporary relevance that was perceptive. But it was Ebrahim Alkazi who turned Tughlak into a magisterial splendour with his staging of it amid the ruins of Purana Qila in Delhi in 1972.

Ultimately, though, it was Karnad’s boundless imagination that made him a playwright without parallel. Who else could think up a cobra in love with a woman? Or a horse reciting the National Anthem? Or the hullabaloo caused by two decapitated men who get their heads fixed back but on the wrong bodies? And also, who else could think of demanding that the Bangalore International Airport be named after Tipu Sultan? Karnad had his share of eccentric ideas. But what emerged through it all was a man who was unselfish. That is a rare distinction these days.

Let us not forget his die hard support for Tippusultan the brutal maurder and religious bigot. Karnad was the modern day Tughlaq