A conservation story from River Cauvery

By B.C. Thimmaiah

On 2018, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified the Orange-Finned or Humpback Mahseer as ‘Critically Endangered.’

Yet, in the protected stretches of the River Cauvery in Kodagu, the species is found in abundance, thanks to the efforts of Coorg Wildlife Society (CWS) and the family of Chendanda S. Ponnappa and his son Chendanda P. Aiyappa. Mahseer conservation in Cauvery has a history that goes back nearly four decades. It began in 1985, when Ponnappa, a member of CWS, asserted at a meeting that Mahseer still thrived in the Cauvery at Dubare and Valnoor.

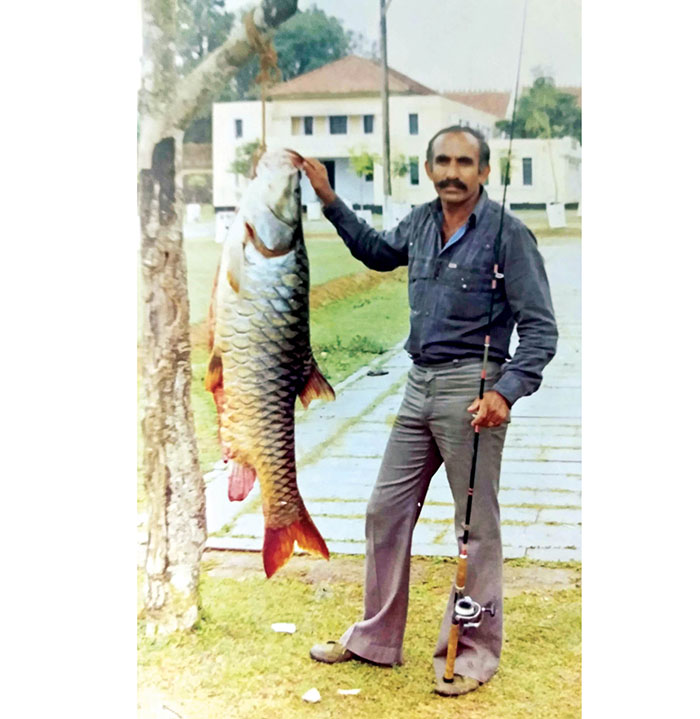

At the time, doubts were raised about the fish’s presence in the river. To settle the debate, Ponnappa landed a 44-kg Mahseer in July 1985 at Valnoor, conclusively proving that the iconic fish — known locally as ‘Bommeen’ or ‘Boltha Meen’ in Kodava Thakk and ‘Bilimeenu’ in Kannada — was very much alive in the river. The Cauvery is home to Golden, Silver and Black Mahseer.

Protected stretch of Cauvery

That single act marked the beginning of organised Mahseer conservation in Kodagu. Soon after, the Coorg Wildlife Society approached the Fisheries Department, which leased a 25-kilometre stretch of the Cauvery, from Siddapur Bridge to Kushalnagar Bridge, to the Society in 1985 and declared it a protected zone for Mahseer.

The move was accompanied by wide publicity against destructive fishing practices such as dynamiting, the use of nets, copper sulphate poisoning and even poisoning with wild fruits, methods that were rampant at the time and posed a serious threat to aquatic life. Once the lease was handed over, such practices were completely banned and strict enforcement followed.

Equally significant was the crackdown on riverbank encroachments. After the declaration of the Mahseer protected zone, previously unreported encroachments were identified and cleared. “The CWS deserves full credit for making the riverbanks along the protected stretch encroachment-free,” Aiyappa told Star of Mysore.

Science-backed conservation model

C.S. Ponnappa oversaw the conservation operations in the initial years, laying the foundation for what would later evolve into a science-backed conservation model. Subsequent studies established that the Humpback Mahseer, endemic to the Cauvery, is among the largest freshwater fish in India, growing up to 63-kg.

“For nearly 20 years, the CWS successfully protected the original 25-km stretch. Encouraged by the results, the Fisheries Department later extended our responsibility to a nearly 100-km stretch of the Cauvery from Bethri Bridge to Kushalnagar and the Barapole River. While we managed and protected about 95-km for a decade, logistical challenges forced us to withdraw from Barapole,” Aiyappa revealed.

“Conservation along the Bethri-Kushalnagar stretch also proved difficult due to dense coffee estates on either side and the influx of a floating population. Eventually, efforts were refocused on the original stretch between Siddapur and Kushalnagar,” he said.

“Over the past decade, this protected stretch was further extended to 35-km, up to Shirangala. Today, Mahseer is conserved from Siddapur Bridge to Shirangala till the River Cauvery leaves Kodagu,” Aiyappa noted.

Radio-collaring efforts

One of the most significant contributions of the CWS has been scientific research. The Mahseer telemetry study conducted was the first-of-its-kind in India.

Over 40 Mahseers were caught, fitted with radio transmitters and released back into the river to study. However, known for their intelligence, the fish often rubbed the transmitters against rocks and managed to dislodge them.

Despite these challenges, researchers were able to gather valuable data on migration patterns and habitat preferences during high-water conditions.

National institutions such as the Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute and the Central Institute of Freshwater Aquaculture undertook five years of research in the region.

“Until then, there was little data on the upper reaches of the Cauvery, covering water quality across seasons, sediment composition, riparian vegetation and fish diversity. We supported these studies by providing staff and access to field locations. The findings, expected to be released soon, will offer deeper insights into the river’s ecology, including its insect and plant life,” Aiyappa revealed.

Ban on mining, fishing

“We also collaborated with Carleton University, Canada, on a study examining post-release mortality of Mahseer. The results were encouraging, showing a survival rate of 99.5 percent among fish that were caught and released,” Conservationist Aiyappa said.

Legal intervention has also played a conservation role. An order was obtained from the Karnataka High Court banning sand mining in Mahseer-protected areas. Four full-time river watchers now patrol the stretch, monitoring illegal activities and gathering information on netting.

“With dynamiting and chemical poisoning classified as serious offences, such activities have virtually disappeared from the protected zones. Public awareness has grown to the extent that locals now alert authorities to any violations,” he noted.

Mahseer, Aiyappa points out, is among the most intelligent freshwater fish. Their survival over millions of years is testimony to their adaptability. The Mahseer derives its name from Sanskrit — ‘mahat’ (big) and ‘śiras’ (head).

Conservation efforts here go beyond a single species. The Cauvery is home to over 100 endemic fish species, all of which are protected under the current ecosystem-based conservation model. By minimising human intervention, aquatic life has begun to thrive across the protected stretches.

Mahseer is not edible. Wherever they thrive, invasive species such as Catfish and Tilapia fail to survive. Eating Mahseer causes persistent vomiting, possibly due to its high protein content or toxic fat composition. Today, the fish is globally renowned as a sport species rather than a food fish.

Since 2018, following directions from the Fisheries Department, Aiyappa has been attempting to breed the Humpback Mahseer and Orange-Finned Mahseer in captivity. Several attempts failed due to unforeseen challenges.

“Currently, juvenile fish have been collected and are being reared in controlled conditions at the Mahseer hatchery in Harangi,” he said.

This effort is ongoing to develop brood stock. Aiyappa remains hopeful. If successful, even 100 fishlings released into the wild would mark the first instance of captive breeding of a critically endangered freshwater fish in India.

The presence of Mahseer of various sizes in the protected areas already points to a positive trend, proof that the species is breeding, returning and repopulating the Cauvery under sustained conservation efforts.

Recent Comments